ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 19 April. Click Here for more information.

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 What is the CBAM?

- 3 What are the arguments in supporting the implementation of CBAM?

- 4 What are the arguments against the implementation of CBAM?

- 5 How does CBAM affect other countries’ carbon pricing mechanisms?

- 6 Why is India worried about the CBAM?

- 7 How is India planning to tackle CBAM?

- 8 What should be done?

| For 7PM Editorial Archives click HERE → |

Introduction

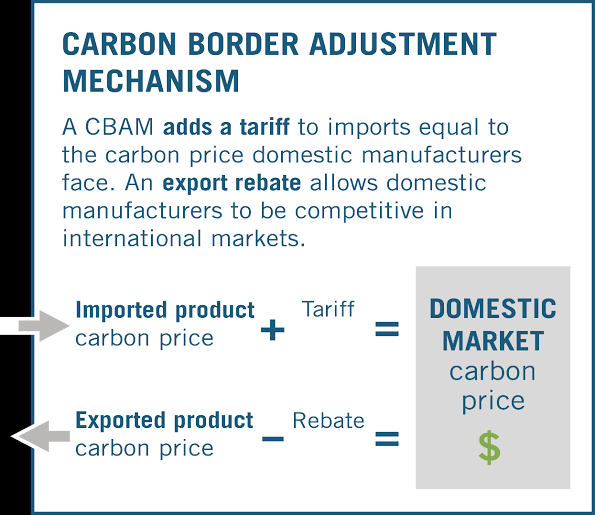

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), recently implemented by the European Union (EU), has significant implications for countries like India. CBAM imposes a carbon cost on high-emission imports, potentially affecting India’s export competitiveness. This new regulation, aimed at preventing carbon leakage, raises concerns about compatibility with existing trade norms and commitments under the Paris Agreement. Understanding the potential impact of CBAM on India and how the country responds is crucial in the broader context of global climate policy and trade.

What is the CBAM?

| Read here: Common Border Adjustment Mechanism |

What are the arguments in supporting the implementation of CBAM?

Promotes decarbonisation globally: The CBAM provides an incentive for countries to reduce their carbon emissions. For example, if a country wants to export steel to the EU, the policy imposes an extra cost if the steel is produced using carbon-intensive processes. This encourages manufacturers to adopt cleaner, less carbon-intensive methods of production.

Prevents carbon leakage: CBAM prevents “carbon leakage”, the phenomenon where companies transfer their operations to countries with less stringent emissions regulations. For example, if a cement manufacturer moves from the EU to a country with fewer regulations, it might increase emissions. The CBAM discourages this by imposing a border tax on carbon-intensive imported goods.

Level playing field for businesses: The CBAM helps create a level playing field between domestic businesses in the EU and foreign companies. For instance, a European aluminium producer that follows strict emission rules would be at a disadvantage if competitors from other countries with less stringent rules could sell their products in the EU without any penalties. CBAM ensures foreign producers are also subject to a carbon cost, ensuring fairness.

Revenue generation for climate initiatives: CBAM will generate revenue through border taxes on carbon-intensive goods. This can be used to fund climate initiatives or capacity-building measures in developing countries or Least Developed Countries (LDCs) if the EU decides to allocate it in this manner.

Stimulates innovation in clean technologies: CBAM can stimulate innovation in clean technologies. Faced with a potential CBAM charge, industries may be motivated to invest in new technologies to reduce their carbon emissions. For instance, the fertiliser industry might accelerate research into low-carbon or carbon-free production processes to lower their CBAM costs.

Encourages other countries to adopt carbon pricing: CBAM may encourage other countries to implement their own carbon pricing mechanisms. The aim is to avoid CBAM charges, as goods from countries with equivalent carbon pricing mechanisms are exempt. This could potentially lead to the broad adoption of carbon pricing, further facilitating global decarbonisation.

| Must read: EU’s carbon border tax – Explained, pointwise |

What are the arguments against the implementation of CBAM?

Discrimination against developing countries: One key concern about the CBAM is that it could unfairly disadvantage developing countries and least developed countries (LDCs), which might lack the capacity to meet its requirements. For example, a steel producer in a developing country might not have the resources to reduce its carbon emissions to EU standards, which could put it at a disadvantage in the international market.

Contradiction with multilateral agreements: CBAM may contradict existing multilateral climate and trade agreements, including the Paris Agreement and World Trade Organization (WTO) principles. For instance, the Paris Agreement calls for ‘Common but Differentiated Responsibilities’, allowing countries at different stages of development to set their own emissions targets. CBAM doesn’t offer such differentiation, possibly violating this principle.

Potential for trade disputes: CBAM could spark trade disputes, as it appears to contravene the WTO’s non-discrimination principles. Countries could challenge the CBAM at the WTO, arguing it discriminates against ‘like’ goods based on their carbon content.

Complicated implementation: The implementation of CBAM could be complex and challenging, particularly for countries with less administrative and institutional capability. For example, the need to establish rules of origin to account for carbon content for every part and component at the point of origin would be a formidable task for countries involved in complex global value chains.

Possibility of retaliatory measures: There’s a risk that countries affected by the CBAM might respond with retaliatory measures, such as their own carbon border taxes. This could escalate into a trade war, complicating international trade and potentially harming global economic growth.

Questionable justification: Some critics question the basic premise of the CBAM, arguing there’s insufficient evidence of significant carbon leakage to justify it. Critics contend that other factors, such as labor costs, regulatory transparency, and stability, often carry more weight in companies’ location decisions than environmental regulations.

| Read more: A multi-pronged counter is warranted to tackle the EU’s carbon tax plans |

How does CBAM affect other countries’ carbon pricing mechanisms?

Undermining other carbon pricing mechanisms: The CBAM can undermine other countries’ carbon pricing mechanisms by setting a global price standard. As the CBAM only recognizes the EU Emission Trading System and equivalent mechanisms, countries using different forms of climate regulation may find their efforts devalued.

Imposing additional burden on developing countries: Many developing countries lack the institutional capacity to set up a comprehensive accounting and reporting system for carbon emissions, a requirement under the CBAM. This imposes an additional burden on these nations and could potentially hamper their own climate action initiatives.

Questioning “Equivalence”: The concept of “equivalence” becomes tricky with the introduction of CBAM. Countries that have opted for different forms of climate regulation under their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) may struggle to ensure “equivalence” in terms of carbon pricing, potentially leading to an uneven playing field. This will in turn create trade inequities.

The challenge of “Extraterritorial Effects”: The CBAM raises critical questions regarding extraterritorial effects, given that it implicitly assumes or enforces compliance with EU norms on countries outside its jurisdiction. This could lead to tensions in international climate agreements and trade relations.

Why is India worried about the CBAM?

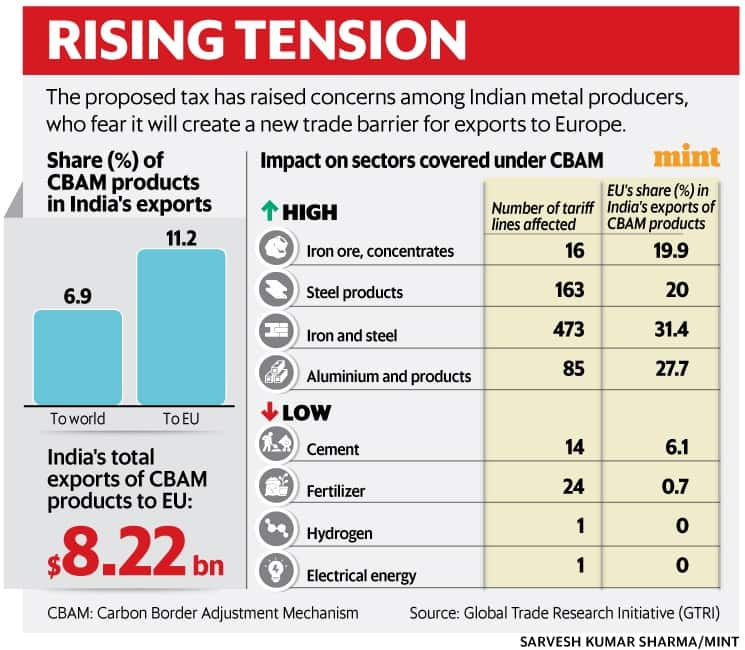

Potential impact on key industries: India, being a major global producer of steel and aluminium, is concerned about the impact of CBAM on these industries. The CBAM might put Indian producers at a disadvantage as they may find it more challenging to meet the EU’s carbon standards.

A barrier to free trade: India is currently in the process of negotiating a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU. There’s a worry that while tariffs are being eliminated under the FTA, the CBAM could act as a non-tariff barrier, impacting the expected benefits of the agreement.

Transparency concerns: India also raises concerns over the transparency of the carbon tax calculation under CBAM. The EU’s one-size-fits-all approach may not take into account factors like per capita pollution, forest cover, and sustainable living, which are relevant in the Indian context.

Risk of retaliation and trade disputes: Lastly, India, like many other countries, might consider retaliatory measures against the EU’s CBAM. This could lead to trade disputes and potentially harm relations between India and the EU.

| Read more: Why EU’s carbon levy helps rich countries get richer |

How is India planning to tackle CBAM?

Conducting sectoral analysis: The Indian government plans to undertake a sector-by-sector analysis to assess the impact of the CBAM on its industries. This detailed examination will aid in determining targeted action plans for each potentially affected sector.

Engaging relevant departments: India is roping in multiple departments, such as the Climate Change Finance Unit of the Department of Economic Affairs and the Steel Ministry, to collaboratively analyze the potential issues and formulate suitable solutions.

Incorporating CBAM into FTA Negotiations: India is considering including CBAM discussions in the ongoing negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement with the EU. This approach aims to ensure that while tariffs are being eliminated under the FTA, the CBAM doesn’t pose additional barriers to trade.

Demanding transparency: India is keen to ensure that the EU provides transparency in how the carbon tax under the CBAM is calculated for different sectors. It insists that factors like per capita pollution, forest cover, and sustainable living practices should also be considered in the assessment.

Building alliances with developing nations: In its strategy to tackle the CBAM, India is also planning to join forces with other developing nations, such as South Africa. This collective approach will help present a united front in discussions and negotiations with the EU, strengthening their stance and addressing common concerns effectively.

| Read more: Exporting into a world with carbon tax |

What should be done?

Adopting uniform carbon pricing: To avoid the complexities related to the CBAM, countries should work towards a global agreement on uniform carbon pricing. This will not only create a level playing field but also avoid potential disputes.

Capacity building in developing countries: Given the difficulties in accounting and reporting the carbon emissions of production processes, efforts should be made at a global level to build the institutional capabilities of developing nations and least-developed countries.

Balancing trade and climate action: There is a need for better coordination and balance between trade policies and climate action commitments. Policies need to be designed such that they do not contradict but complement each other.

Revisiting multilateral agreements: Existing multilateral agreements on trade and climate change may need to be revisited and potentially revised to align them with new climate realities and mechanisms like the CBAM.

Establishing clear rules of origin: If carbon border adjustments become widespread, there will be a need for clear, transparent, and fair rules of origin to account for the carbon content of goods, especially in complex global value chains.

Sources: Live Mint (Article 1 and Article 2), The Hindu (Article 1, Article 2 and Article 3), The Hindu Businessline (Article 1 and Article 2), Business Standard, New Climate, North Africa Post and WEF

Syllabus: GS 3: Environment and Bio-diversity – Environmental pollution and degradation.