ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 19 April. Click Here for more information.

Contents

| For 7PM Editorial Archives click HERE → |

Introduction

The COP27 of the UNFCCC concluded recently in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. The only remarkable outcome of the Summit was announcement regarding setting up on Loss and Damage Fund. Skeptics, however, are wary that the real challenge is operationalizing the Fund, and there is a high possibility that Loss and Damage Fund may also end up an empty promise like other Climate Finance measures. At the opening of the COP27, former Vice President of the US and Environmentalist, Mr. Al Gore remarked that, “We are not doing enough“, in context of efforts of Developed nations. Developed nations have continued to dilute the climate negotiations and are increasingly put the burden of addressing climate change on developing nations including India. Climate experts and environmentalists have lamented the lack of progress on important issues of Climate Finance, and gradual shifting of burden of climate action on developing nations. This is being termed as violative of Climate Justice.

What is the meaning of Climate Justice?

Climate justice is a term used for framing global warming as an ethical and political issue, rather than one that is purely environmental or physical in nature.

‘Climate Justice’ acknowledges climate change can have differing social, economic, public health, and other adverse impacts on underprivileged populations. The impacts of climate change are not borne equally or fairly, between rich and poor, women and men, and older and younger generations. From extreme weather to rising sea levels, the effects of climate change often have disproportionate effects on historically marginalized or underserved communities.

Pursuing climate justice means addressing social, gender, economic, intergenerational and environmental injustice. All the dimensions of injustice are interconnected with each other and must be acknowledged in order to address them holistically e.g., some climate projects inadvertently create climate injustices when local communities are displaced for a conservation or renewable energy initiative.

Advocates for climate justice are striving to have these inequities addressed through long-term mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Climate Justice can be summarised under Four types of Justice:

Procedural Climate Justice: It is associated with fair, accountable, and clear ways to make decisions about the effects of climate change and how to deal with them. It is imperative to have fair procedures in place to make sure that goods are distributed fairly and in a way that is open and accountable. This can be ensured by due process, public participation, and representative justice. This can include access to information, access to and meaningful participation in decision-making, lack of bias on the part of decision-makers. It includes ideas like “transparency”, “fair representation”, “impartiality”, and “objectivity”.

Distributive Climate Justice: This aspect of justice deals with how costs and benefits of climate change are shared. There are three main aspects of distribution: (a) Identifying the goods that are being distributed (e.g. food, clothing, water, power, wealth, or respect); (b) Identifying the entities between which they are to be distributed (e.g. members of certain communities or stakeholders, certain generations, all of humankind); (c) Identifying the most appropriate mode of distribution (e.g. status, need, merit, rights, or ascriptive and social identities).

Recognition Climate Justice: It is focused on recognition of difference. It means identifying vulnerable people whose vulnerability may be worsened as a result of a process such as a low- carbon transition. Recognition Climate Justice places emphasis on understanding differences alongside protecting equal rights for all, especially given uneven capacity to defend rights.

Intergenerational Climate Justice: It was recognized in the Brundtland Report ‘Our Common Future’ (1987) which conceived of sustainable development as being about the ability of current generations to meet their needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Source: Center for Climate Justice

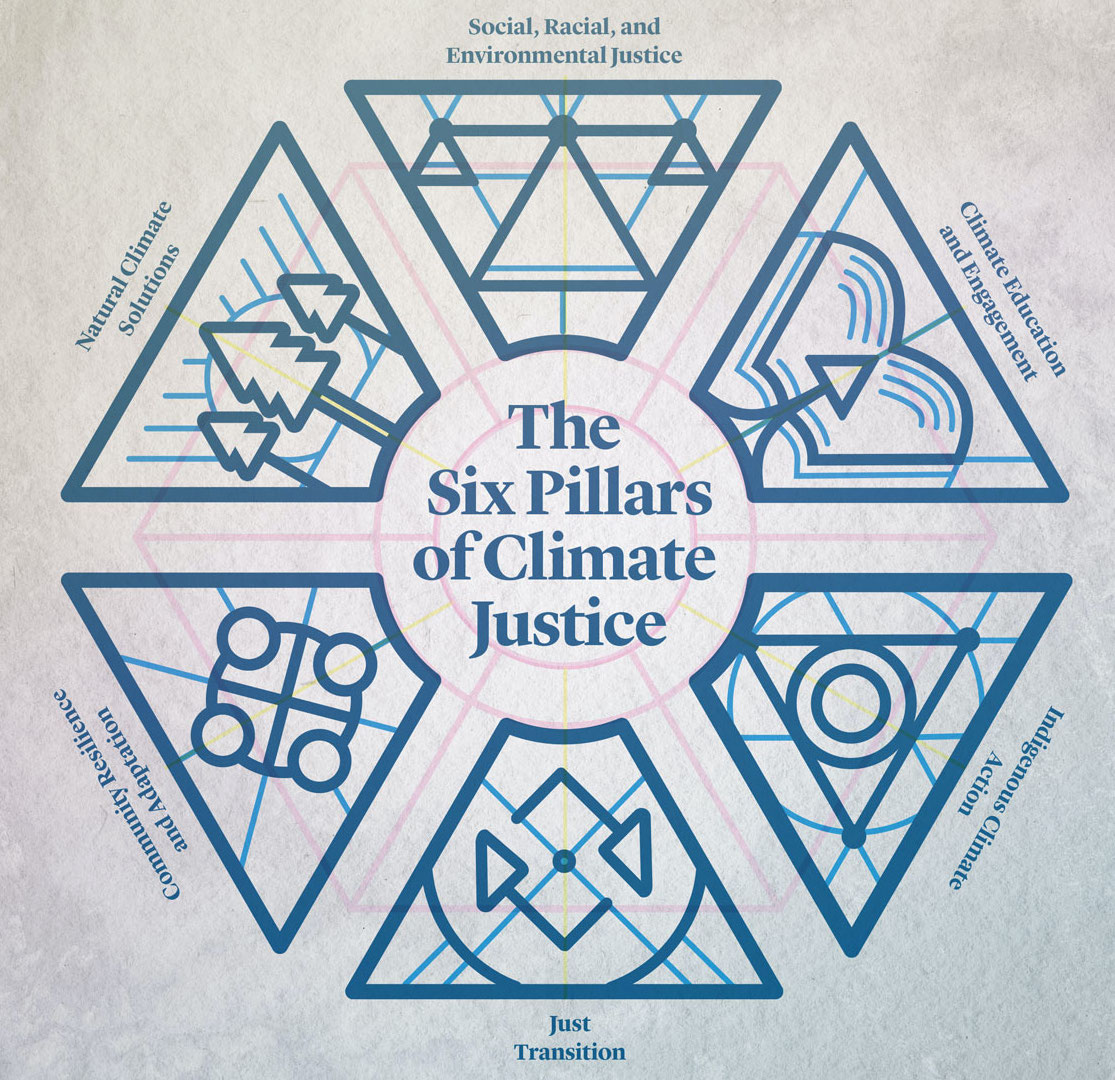

The Center for Climate Justice (University of California) has identified 6 Pillars of Climate Justice:

Just Transition: A just transition represents the transition of fossil fuel-based economies to equitable, regenerative, renewable energy-based systems.

Social Racial and Environmental Justice: It recognizes the disproportionate impacts of climate change on low-income and poor communities around the world, the people and places least responsible for the problem.

Indigenous Climate Action: Indigenous communities around the world are facing some of the most severe climate impacts. Indigenous communities are deeply reliant on their surrounding ecosystems for their lives and livelihoods. Indigenous Peoples are leading efforts in climate change mitigation and adaptation across the globe Climate Action should acknowledge their knowledge and role.

Community Resilience and Adaptation: Community resilience and adaptation must be viewed from a perspective of social justice and equity. This would inspire models such as food sovereignty, common property forest management, and energy democracy. It would support local communities in developing their own solutions and allow them to benefit directly from local climate action.

Natural Climate Solutions: From a climate justice perspective, natural climate solutions take a systems approach and include regenerative farming, agroforestry, permaculture, urban gardens, and forest restoration.

Climate Education and Engagement: Widespread climate education and engagement is fundamental to addressing the root causes of climate change. A populace better educated about climate justice will fully understand why viewing climate change from a social justice and equity perspective is the best hope for solving the climate crisis.

What is the meaning of Intergenerational and Intragenerational Equity?

Intragenerational and intergenerational equity are both time-based concepts.

Intergenerational Equity refers to the balance between present and future generations. Intragenerational Equity refers to the balance between the rich and poor of the current generation.

Sustainable equity seeks to strike a proper balance between the two.

Intergenerational equity is linked to fair utilization of resources by human generations in past, present and future. It tries to construct a balance of consumption of resources by existing societies and the future generations. It is concerned with growing degradation of environment and depletion of resources. In this context, UN’s concept of sustainable development is linked with Intergenerational Equity.

Intra-generational Equity deals with the equality among the same generations as far as the utilization of resources are concern. It includes fair utilization of global resources among the human beings of the present generation.

It is reflected in Principle 6 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, mandating particular priority for the special situation and needs of developing countries, particularly the least developed and those most environmentally vulnerable.

What are the challenges in ensuring Climate Justice?

Gradual Dilution of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR): Article 3 of the UNFCCC recognizes the principle of CBDR based on differences between developed and developing countries in terms of their current circumstances and historical contributions. However, developed countries keep on pushing for higher commitments by developing countries e.g., Western nations pushed for ‘phase-out’ of coal at Glasgow 2021 (before agreeing for ‘phase-down’). Coal is a cheap source and phasing-out of coal imposes big costs on developing countries.

Avoidance of Binding Targets: The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement are voluntary in nature. They are not binding and legally enforceable. Kyoto Protocol had binding targets for developed countries but it has been non-functional. Developed countries by avoiding binding targets have reneged on their responsibility owing to historical contributions.

Shortfall in Climate Finance: Despite their pledge, the developed countries have failed to provide US$ 100 billion per year for Climate Finance. Climate experts contend that US$ 100 billion per year is minuscule to address Climate Change. IPCC estimates that US$ 1.6–3.8 trillion is required annually to avoid warming exceeding 1.5°C.

| Read More: Climate Finance: Meaning, Need and Challenges – Explained, pointwise |

How can Climate Justice be ensured?

First, the intragenerational equity can be addressed through a predictable and assured Climate Finance. There can be binding targets on developed countries to provide funding to vulnerable countries, commensurate to their historical contributions.

Second, the Climate Finance can be augmented by technology transfer to the developing nations and accelerating their transition to low-carbon economies.

Third, ‘Climate-induced Disasters’ may become the ‘new normal’. Climate Justice concerns should be mainstreamed into disaster relief efforts. Loss and Damage Fund should recognize principles of Climate Justice and should provide relief without any conditions.

Fourth, Developed countries, recognizing their historical responsibility, should take binding targets in reducing their emissions.

Fifth, Developing countries should also focus on ensuring intra-generational equity within their own societies. They should take steps for climate education and engagement.

Conclusion

Climate Justice has remained elusive in the present framework of Climate Negotiations and Action. The developed countries have been gradually shifting the onus on the poor and developing nations. There is a need for course correction. Non-recognition of Climate Justice in Climate Action Framework will eventually lead to failure in achieving the goals agreed under the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement.

Syllabus: GS III, Conservation, Environmental Pollution and Degradation.

Source: The Hindu, Institute of Development Studies, LSE, Centre for Climate Justice