ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 19 April. Click Here for more information.

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Evolution of Local Governance in India

- 3 What is the structure of Local Governance in India?

- 4 What are the roles of Panchayati Raj Institution (PRIs)/Local Governance Bodies?

- 5 What are the challenges in working of Local Government Bodies?

- 6 What steps can be taken going ahead?

- 7 Conclusion

| For 7PM Editorial Archives click HERE → |

Introduction

It is almost 30 years since the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendment Acts, creating the new Local Governance Framework in India, were made operational in April 1993. The Acts, focused on enabling democratic decentralization, have provisions that devolved a range of powers and responsibilities to local elected bodies and made them accountable to the people for their implementation. The new system of local governance has proved to be remarkably beneficial in some aspects. Yet, there are some lacunae, especially in the implementation of several provisions, which has limited the effectiveness of these reforms.

Evolution of Local Governance in India

There is long evolutionary history of local governance in India. Evidence from the Rig-Veda (1700 BC) shows self-governing village organisations called Sabhas. In time, these bodies became panchayats (council of five). The decentralization of authority was present in the Mauryan to Gupta dynasties. The British also tried to establish decentralized systems, albeit with very little powers. The Royal Commission on Decentralization (1907) under the chairmanship of Sir H. W. Primrose recognized the importance of panchayats at the village level. Under the Government of India Act, 1935 Provincial Governments were responsible for local governance. They enacted legislations but little powers were provided to Panchayats

The framers of the Constitution of India included Article 40 among the Directive Principles: “The state shall organise village panchayats and endow them with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to function as units of self-government”. Four committees (between 1957 to 1986) conceptualised local self-government in India; Balwant Rai Mehta Committee (1957), the Ashok Mehta Committee (1977–1984), GVK Rao Committee (1985), and the LM Singhvi Committee (1986).

Eventually, the local Governance was given Constitutional Status with the 73rd/74th Constitutional Amendment Acts in 1992. The Amendment Acts of 1992 added two new parts IX and IX-A to the Constitution. Two new Schedules 11 and 12 were also added which contain the lists of functional items of Panchayats and Municipalities.

What is the structure of Local Governance in India?

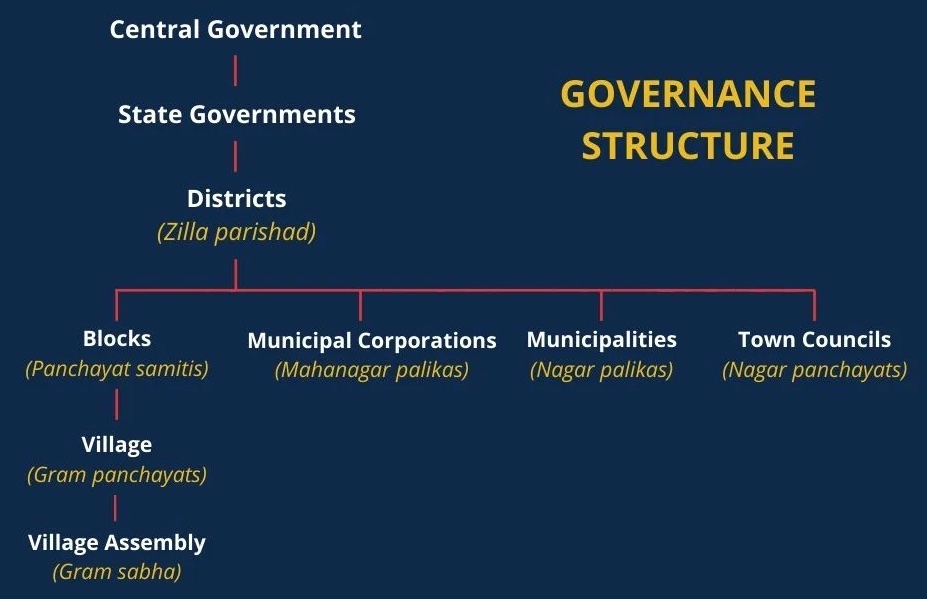

The 73rd/74th Amendment Acts established a three-tier system of Panchayati Raj in every state – at the village, intermediate and district levels.

For rural areas, there are three nested bodies. At the top is the District Council or Zilla Parishad, which is made up of a cluster of Block Councils or Panchayat Samitis, which in turn, are made up of village councils or Gram Panchayats. Each village has a village assembly or gram sabha comprising all adults in the village. Gram Sabha has the power to directly elect members of the panchayat. States with a population of less than two million may choose to have a two-tiered structure, without the intermediate block-level institution.

In urban areas, there are three types of local bodies: Municipal Corporations (Mahanagar Palikas for areas with a population of more than one million), Municipal Councils/Municipalities (Nagar Palikas for areas with less than a million people), and Town Councils (Nagar Panchayats for areas transitioning from rural to urban).

Scheduled and Tribal areas are legally exempt from implementing the Panchayati Raj system. The Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas (PESA) Act, 1996 provides for the extension of the 73rd Amendment (with certain modifications and exceptions) to tribal and forested areas across 10 states of India, (excluding tribal areas in the states of Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram, which are governed by District or Regional Councils). These provisions have been put in place to protect customary law, social and religious practices, and traditional management practices of community resources.

A minimum of one-third of the seats in all local bodies are reserved for women. Seats are also reserved for people belonging to scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, and other backward classes in proportion to their population.

What are the roles of Panchayati Raj Institution (PRIs)/Local Governance Bodies?

PRIs play a crucial role in rural development and perform the following roles: (a) Administrative activities such as the maintenance of village records, the construction, maintenance, and repair of roads, tanks, wells, and so on; (b) Improving socio-economic welfare through the promotion of rural industries, health, education, women and child welfare, among others; (c) Judicial functions such as trying petty civil and criminal cases such as minor thefts and money disputes are also performed either by separate adalati or nyaya panchayats, or by gram panchayats.

What are the challenges in working of Local Government Bodies?

Functional Challenges: The power to devolve functions to local governments rests with the State Government. Most States have not devolved adequate functions to local government bodies. This has severely affected the system’s efficiency and effectiveness. State Governments have created parallel structures for the implementation of projects around agriculture, health, and education, which undermines the status of local bodies. Local bodies lack the support systems necessary to carry out their mandates. The 74th amendment requires a District Planning Committee to be set up in each district, so that the development plans prepared by the panchayats and urban local bodies can be consolidated and integrated. According to a study by the India Development Review (IDR, a think tank), District Planning Committees are non-functional in 9 states, and failed to prepare integrated plans in 15 states.

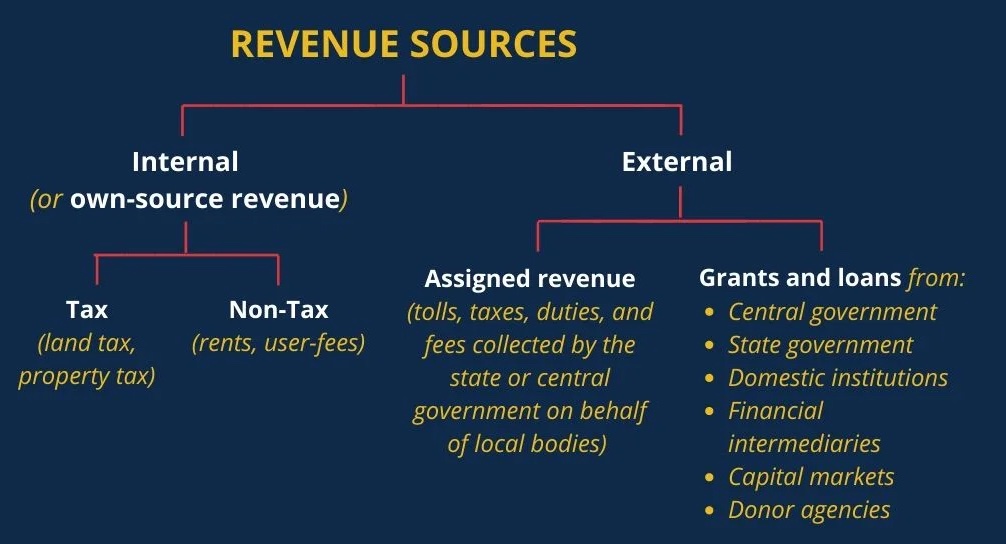

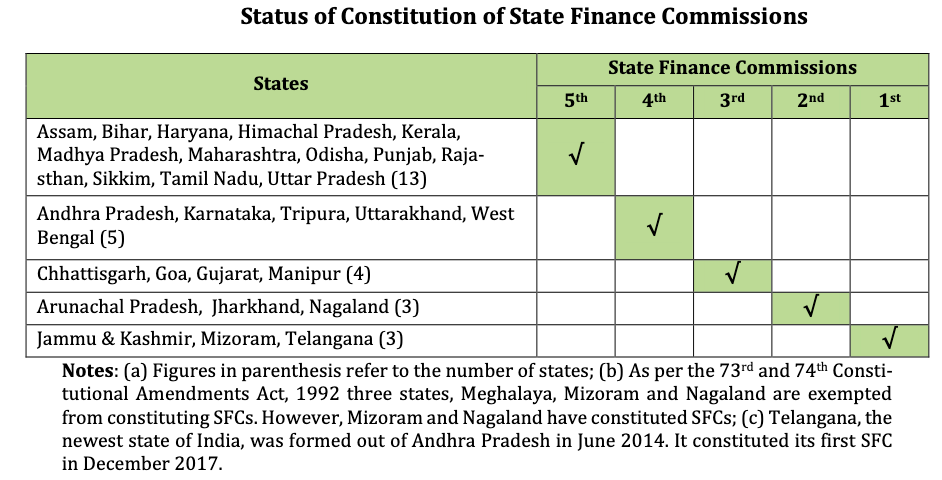

Financial Challenges: (a) Local government expenditure as a percentage of GDP is only 2%. This is extremely low compared to other major economies like China (11%) and Brazil (7%); (b) Most local bodies, both rural and urban are unable to generate adequate funds from their internal sources, and are therefore extremely dependent on external sources for funding. Studies show that around 80-95% of revenue is obtained from external sources, particularly State and Union Government loans and grants; (c) The volume of money set apart for them is inadequate to meet their basic requirements. Local Governments are starved of resources. The Union Finance Commissions have made desirable recommendations, but the actual devolution of funds has been very poor. Not more than 5% of the divisible pool of Union taxes is given to local governments; (d) The devolution of funds is associated with conditionalities that bind them to specific uses. (i.e., top driven schemes of Union/State Governments, rather than based on local needs). The Government-appointed officers have complete control over spending of funds instead of the elected representatives of local governments; (e) State Finance Commissions are not established as per Constitutional requirements (constitute every 5 years). By 2014-15, States should have created 5th State Finance Commission (SFC) in their respective States, but only 13 had created them. By 2019, when 6th State Finance Commission should have been constituted, some States were yet to create 3rd or 4th Commissions. J&K had created only 1 SFC by April 2019; (f) Some experts argue that Local governments are reluctant to collect property taxes and user charges because of fear of backlash from public. They are happy to implement top-down programmes because they know that if they collect taxes, their electoral prospects will be hampered.

Source: NIPFP. Status of Constitution of State Finance Commissions as of April 2019.

Functionary Challenges: (a) Every local government needs to have organisational capacity, by way of staff such as office and clerical staff and social mobilisers. Staffing of local governments is scanty. Many panchayats share a single secretary, who is often overburdened; (b) Technology has been used to centralize the delivery of local services which has been detrimental to local decision-making.

Other Challenges: (a) Criminal elements and contractors are attracted to local government elections especially in urban areas. They are able to win elections through corrupt means, as local elections do not get same scrutiny as State Assembly or General Elections; (b) Elections to the local bodies are often delayed. For long period of times there are no functional local governments; (c) Despite a relatively higher level of literacy and educational standard, city-dwellers do not take adequate interest in the functioning of the urban government bodies e.g., the turnout in Municipal Elections in Delhi and Mumbai in 2017 was only 53% and 55% respectively; (d) While women have been empowered with representation through reservation of seats, the ‘Sarpanch Pati‘ syndrome limits the effectiveness. (‘Sarpanch Pati’ syndrome: Women Sarpanch is only nominal head, the male relative (generally husband) wield actual power).

What steps can be taken going ahead?

First, the provisions of 73rd/74th Constitutional Amendments should be implemented in true spirit. State Finance Commissions should be regularly constituted with clearly defined Terms of Reference (ToR). ToR should include recommendation to devolve more funds and make the functioning of local bodies more effective. Adequate powers to raise own revenues should be devolved to local governments.

Second, the elections should be held at regular intervals without any delay. State Governments and State Election Commissions must be held accountable for delays.

Third, Gram Sabhas and wards committees (in urban areas) have to be revitalized. Consultations with the grama sabha could be organised through smaller discussions where everybody can participate to make them inclusive. New media of communication like social media groups could be used for facilitating discussions between members of a grama sabha/ward committees.

Fourth, local government organisational structures have to be strengthened. Panchayats are burdened with a huge amount of work that other departments thrust on them, without being compensated for the extra administrative costs. Local governments must be enabled to hold State departments accountable and to provide quality, corruption free service to them.

Fifth, there is a need to improve capabilities of human resources through training, process consultation, action research methods and workshops.

Sixth, citizen participation and engagement in local governance can be enhanced with the help of NGOs and civil society organizations. Citizens also need to be informed about the functioning and consequences of decisions taken by the local government bodies. The general public also need to be informed about the role of the service providers, the cost of services, the sources of their financing etc.

Conclusion

Empowering the local bodies for Local Governance has been one of the most progressive reform since Independence. It has envisioned to place the governing power in the hands of the general populace. Just like every other reform, this one has a few loopholes in it. Nevertheless, if these gaps are removed, the present local governance system can truly empower the citizens and support the inclusive growth.

Syllabus: GS II, Devolution of powers and finances up to local levels and challenges therein.

Source: The Hindu, The Hindu, The Hindu BusinessLine, Economic Times, NIPFP