ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 19 April. Click Here for more information.

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 What is the SC Judgment regarding Eco-Sensitive Zones (ESZs)?

- 3 What are the benefits of Eco-Sensitive Zones (ESZs)?

- 4 What is the conflict between Forest Conservation and Forest Rights?

- 5 What can be done to resolve the conflict between Forest Conservation and Forest Rights?

- 6 Conclusion

| For 7PM Editorial Archives click HERE → |

Introduction

In June 2022, the Supreme Court had directed that every national park and wildlife sanctuary in the country will have a mandatory Eco-Sensitive Zone (ESZ) of at least one kilometre starting from its demarcated boundaries. The decision was made in response to a petition to protect forest lands in Tamil Nadu’s Nilgiris district. However, the creation of these zones has provoked protests in Kerala and some other areas. Rights activists have criticized this rights-negating ‘fortress conservation model’, as such models of forest conservation tend to deny the rights of traditional forest-dwelling communities. Critics argue that powers given to conservation authorities under the Forest Conservation Act has led to labelling of traditional forest dwellers as ‘encroachers’ in their own areas and denied them equitable access to forests’ resources. Forest Rights Act was enacted to recognize the rights of traditional communities. Yet there has been a conflict between the Forest Rights and Forest Conservation because of lacunae in the implementation of these laws. Hence, there is a need to balance the two aspects, in order to ensure sustainable conservation while preserving rights of the tribals.

What is the SC Judgment regarding Eco-Sensitive Zones (ESZs)?

In June 2022, a 3-Judge bench of the Supreme Court heard a PIL regarding protection of forest land in the Nilgiri Hills (Tamil Nadu). The Supreme Court passed a Judgment regarding the creation of Eco-Sensitive Zones (ESZs) around protected areas. The salient aspects of the rulings were:

First, The Supreme Court directed that no permanent structure will be allowed within the eco-sensitive zone.

Second, Mining within a national wildlife sanctuary or national park cannot be permitted.

Third, If the existing eco-sensitive zone goes beyond the 1 km buffer zone or any statutory instrument prescribes a higher limit, then such extended boundary shall prevail.

Fourth, the SC said that the MoEFCC guidelines are also to be implemented in the area proposed in the draft notification awaiting finalisation and within a 10-km radius of yet-to-be-proposed protected areas. The Guidelines were released in July 2022.

| Read More: Forest Conservation Rules, 2022: Provisions and Concerns – Explained, pointwise |

Fifth, The Court also allowed States to increase or decrease the minimum width of ESZs in the public interest.

Sixth, The Court vested the powers to ensure compliance with the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (PCCF) and the Home Secretary of the State/UT. Within three months, the PCCF was supposed to make a list of all structures in the ESZs and send it to the Supreme Court (this is yet to be done) within 3 months.

What are the benefits of Eco-Sensitive Zones (ESZs)?

Reduce Human-Animal Conflict and Forest Depletion: ESZs help in reducing human-animal conflict by creating buffer zones. Moreover prohibition of certain activities in ESZs helps in better conservation. The local communities in the surrounding areas are also protected and benefited from the protected areas thanks to the core and buffer model of management that the protected areas are based on.

Reduce Externalities of Development Activities: ESZs as buffer zone help in protection of areas adjacent to the protected areas and help mitigate the negative effects of urbanisation and other development activities.

Minimize Damage to Fragile Ecosystems: Declaring certain areas around protected areas to be environmentally sensitive serves the purpose of developing a ‘Shock Absorber’ for the protected area. They also serve the function of a transition zone between areas with higher levels of protection and areas with lower levels of protection.

Conservation: ESZs are also helpful in conservation of endangered species. Restriction of activities in ESZs effectively expand the area available to the threatened species and reduce their vulnerability.

What is the conflict between Forest Conservation and Forest Rights?

Critics argue that the powers granted to Forest Authorities under Forest Conservation has led to their misuse resulting in undermining of the rights of traditional forest dwelling communities (recognized in the Forest Rights Act, (FRA) 2006).

First, critics argue that the Union and State Governments have attempted a series of ‘backdoor’ policy changes in an attempt to roll back the achievements of the FRA e.g., the Governments of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh notified the rules for the administration of “village forests” in 2015. These rules sought to provide a parallel, forest department-dominated procedure by which villages could secure rights over common and collectively managed forests, and, in practice, the forest department would use pressure and monetary incentives to ensure that this process, rather than the statutory procedure under the FRA, would be followed. The guidelines issued in 2015 allowed private companies to take over patches of forestland for growing tree or bamboo crops, with rights arbitrarily limited to 15% of the leased areas.

Second, The Compensatory Afforestation Fund Act was passed in 2016. It provided for the spending of a fund of more than INR 50,000 crore on forestry-related activities that had a direct impact on forest dwellers. The Act didn’t contain the words ‘Forest Rights’. The Government had assured that the rules formulated under the Act will address Forest Rights, but that hasn’t happened.

Third, The Forest Right Act, 2006 was challenged in the Supreme Court by forest conservation groups like Wildlife First and Wildlife Trust of India. They had argued that the FRA facilitates deforestation and illegal encroachment. Critics argue that the Union Government didn’t defend the FRA vigorously. In 2019, the SC ordered the States to summarily evict or take other appropriate legal action against individuals whose land claims have been rejected. The SC stayed the decision after nationwide protests, but hasn’t addressed the fundamental conflict between Forest Rights and Forest Conservation.

Fourth, in 2019, amendments were proposed to the Indian Forest Act, 1927 which, among other things, would empower forest officials to use firearms and to take away forest rights merely through the payment of monetary compensation. These amendments would destroy the essence of Forest Rights.

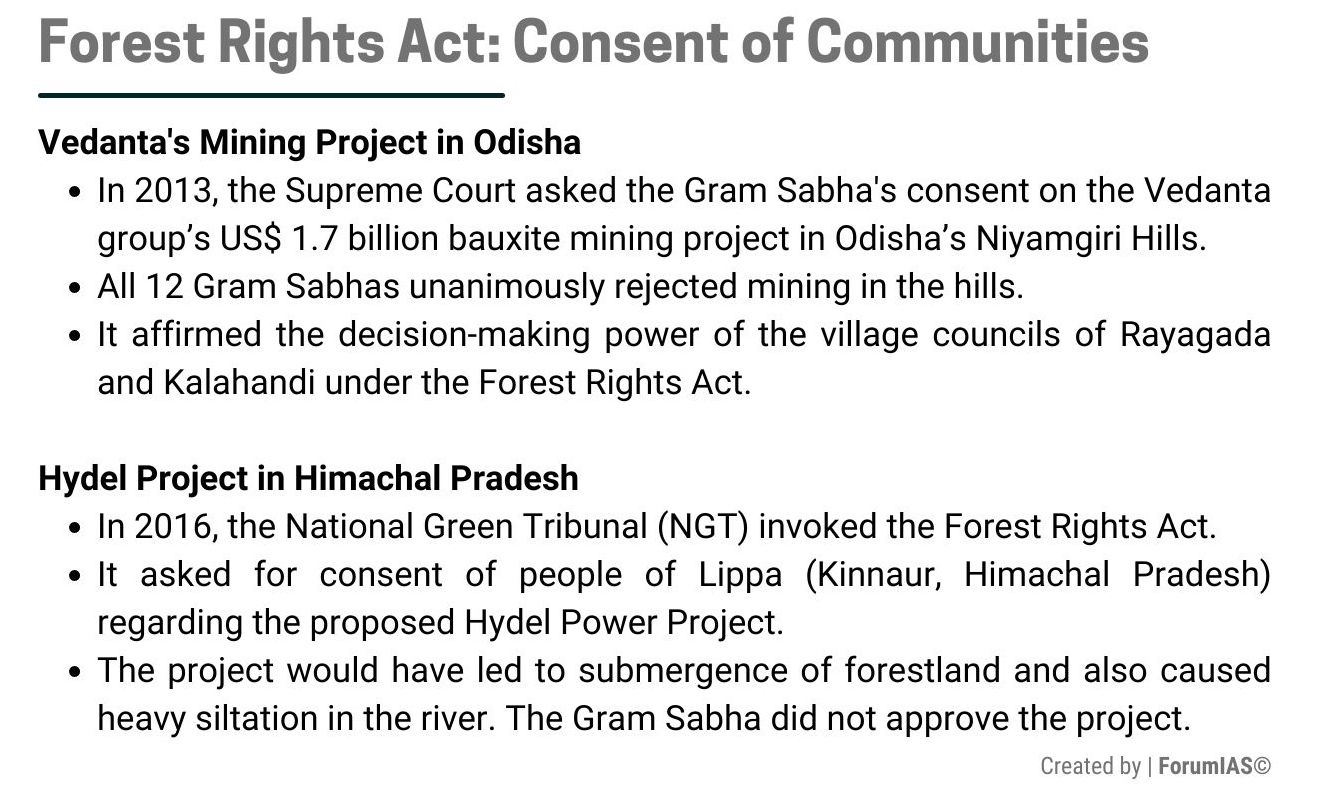

Fifth, The new Forest Conservation Rules were notified in 2022. The wording of new rules implies that it is not mandatory to take the consent of Gram Sabha before diversion of forest. Moreover, the new rules allow the Union Government to permit the clearing of a forest before consulting its inhabitants. This is akin to forced consent, the inhabitants will have no choice but to accept. The National Commission for Scheduled Tribes has asked to put these rules on hold, however the Ministry of Environment hasn’t agreed to this proposal.

| Read More: About Tribal Rights: How We Treat Our First Citizens |

Sixth, the SC ruling regarding the ESZs has meant that all the activities permitted by the guidelines and which are already being carried out can continue only if the PCCF grants permission, and that too within six months of the SC’s order. This period has already expired. Additionally, the SC’s directions have put the lives of many people in the hands of the PCCF, whose authority now extends beyond the forest to revenue lands falling within an ESZ. This has led to protests in Kerala.

What can be done to resolve the conflict between Forest Conservation and Forest Rights?

First, The Government and the Judiciary need to reconcile laws, reaffirm democratic governance, and protect the environment and as well as livelihoods.

Second, A flexible and area-specific minimum limit boundary provision is required. Many environmentalists across the country expressed concern about the mandatory implementation of the Eco-Sensitive Zone (ESZ) for each national park and sanctuary, which appears to be fine, but a fixed minimum limit of one kilometre raises some concerns. The physiography of an area should also be considered for the eco-sensitive zone notification.

Third, The mandated eco-sensitive boundary should be extended to national parks and sanctuaries and to forest patches with better forest cover, good species composition, and a significant presence of wild species.

Fourth, Data must be collected at the ground level. Even though the establishment and upkeep of buffer zones around ecologically sensitive areas are considered to be of the utmost importance, the process is frequently hindered by a lack of trustworthy data collected at ground level. The vast majority of micro-level land use statistics are based on conjecture, with very little input from the ground.

Fifth, A meeting of all States, the Union Government, and the Judiciary is required before the recent judgement is carried out, so that genuine concerns raised by the State Governments can be addressed appropriately, reducing future conflicts.

Sixth, The mining companies must strictly adhere to environmental regulations and practise sustainable mining. At the same time, no mining permits should be issued if any mineral extraction jeopardised the carrying capacity of the protected areas. This should be the approach for all development activities around the protected areas.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s Judgment regarding the provision of ESZs around protected areas has led to protests in many parts of the country, especially in Kerala. This has reignited the debate regarding Forest Rights and Forest Conservation. Both the dimensions are important in the context of protection of forests and sustainable and inclusive development. The Government must take all possible steps for economic development, but such development shouldn’t be at the cost of rights of the poor tribals as well as destruction of forest ecosystems. Hence the effort should be to establish a balance between the two.

Syllabus: GS II, Welfare schemes for vulnerable sections of the population by the Centre and States; GS III, Conservation.

Source: The Hindu, The Hindu, The Hindu, EPW, SCObserver