ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 19 April. Click Here for more information.

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 What is the current International framework regarding management of oceans?

- 3 What is the proposed UN Treaty on High Seas?

- 4 What is the need for the Treaty on High Seas?

- 5 What are the major impediments to the Treaty on High Seas?

- 6 What are the various marine resources?

- 7 What should be the approach going ahead?

| For 7PM Editorial Archives click HERE → |

Introduction

Delegates from 168 countries were involved in negotiating a legally binding treaty to conserve biodiversity in the high seas or the areas beyond national jurisdiction. However, no consensus was reached as the negotiations ended on August 26. Environmental campaigners have called it a “missed opportunity”. The UN Treaty on High Seas is being considered crucial to protect the marine biodiversity amidst rising threats due to anthropogenic activities. It is expected that the treaty will also help mitigate the impact of climate change on oceans. At present, only 1.2% of international waters fall under protected areas. In June 2022, the UN Secretary General had declared an “Ocean Emergency” at the UN Ocean Conference in the backdrop of alarming rate of extinction of marine species.

What is the current International framework regarding management of oceans?

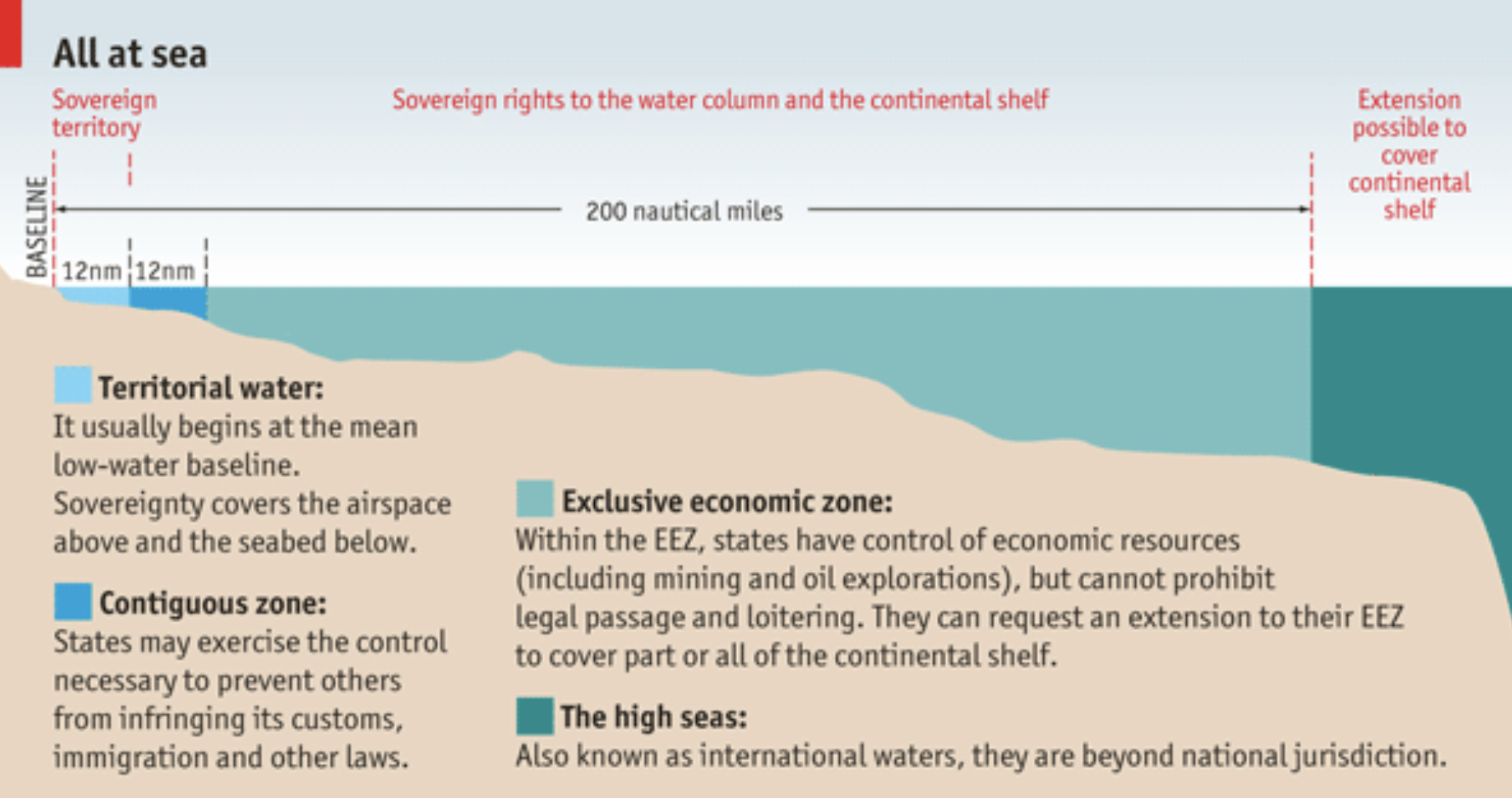

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) lays down a comprehensive regime of law and order in the world’s oceans and seas establishing rules governing all uses of the oceans and their resources. The convention was signed in 1982 and at present it has 168 parties. The 1982 Convention was build on the works of earlier UNCLOS I held in 1956 at Geneva. It had resulted in signing of 4 treaties: (a) Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone; (b) Convention on the Continental Shelf; (c) Convention on the High Seas; (d) Convention on Fishing and Conservation of Living Resources of the High Seas.

However, the 1956 Convention couldn’t decide on the issue of breadth of territorial waters, different countries had adopted different limits (3 mile to more than 12 miles). The 1982 Convention settled the issue with comprehensive coverage of number of associated aspects like setting limits, navigation, archipelagic status and transit regimes, exclusive economic zones (EEZs), continental shelf jurisdiction, deep seabed mining, the exploitation regime, protection of the marine environment, scientific research, and settlement of disputes. The convention set the limit of various areas which include:

Internal Waters: Covers all water and waterways on the landward side of the baseline. The State is free to set laws, regulate use, and use any resource. Foreign vessels have no right of passage within internal waters.

Territorial Waters: Extend up to 12 nautical miles (22 kilometres; 14 miles) from the baseline, the coastal state is free to set laws, regulate use, and use any resource. Vessels have the right of innocent passage through any territorial waters (Passage is not prejudicial to the peace or security of the coastal State, Fishing, polluting, weapons practice, and spying are not innocent).

Contiguous Zone: Extends further 12 nautical miles beyond the territorial waters. The state can enforce laws in four specific areas – customs, taxation, immigration, and pollution.

Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs): EEZs extent up to 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) from the baseline. Within this area, the coastal nation has sole exploitation rights over all natural resources.

There is no formal definition of International Waters or High Seas in international law, but seas beyond EEZ are called as High Seas.

Source: The Economist

The UCNLOS helped in creation of regulating authorities; (a) The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea; (b) The Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf; (c) The International Seabed Authority. It has also outlined general responsibilities towards limiting marine pollution and preserving marine resources.

What is the proposed UN Treaty on High Seas?

The UN High Seas Treaty is being referred to as the ‘Paris Agreement for the Ocean’. It is being negotiated under the UNCLOS.

In 2015, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) had passed a resolution to develop an international legally binding instrument under UNCLOS on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction. In 2017, the UNGA, decided to convene an intergovernmental conference (IGC), with a view to develop the instrument as soon as possible. The negotiations have been going on since 2018 through a series of intergovernmental conferences.

The new treaty will establish a global framework to conserve and manage biodiversity of the High Seas. High seas constitute ~65% of surface and ~95% of volume of oceans.

The treaty is focused on key areas: (a) The conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ); (b) Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs: biological material from plants and animals in the ocean that can have benefits for society, such as pharmaceuticals, industrial processes and food), including questions on benefit-sharing; (c) Area Based Management Tools (ABMT), including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs); (d) Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA); (e) Capacity-building and the Transfer of Marine Technology (CB&TMT) (ensuring less-industrialized countries can meet treaty objectives through a mechanism for sharing marine technology and knowledge).

What is the need for the Treaty on High Seas?

Part XII of UNCLOS (1982) contains special provisions for the protection of the marine environment. However, there are many governance gaps and shortcomings that do not address contemporary challenges e.g., there is no comprehensive, agreed-upon framework governing resource extraction or conservation in the international waters (high seas).

The oceans are facing several challenges: (a) Technological advances enabling greater access to high seas resources are exposing marine ecosystems to severe impacts from fisheries and other extractive industries; (b) Marine life living outside of the 1.2% of protected areas are at risk of exploitation from the increasing threats of climate change, acidification, overfishing and shipping traffic; (c) Chemical, noise and plastic pollution is rising unabated in the seas; (d) According to NASA, 90% of global warming is occurring in the oceans.

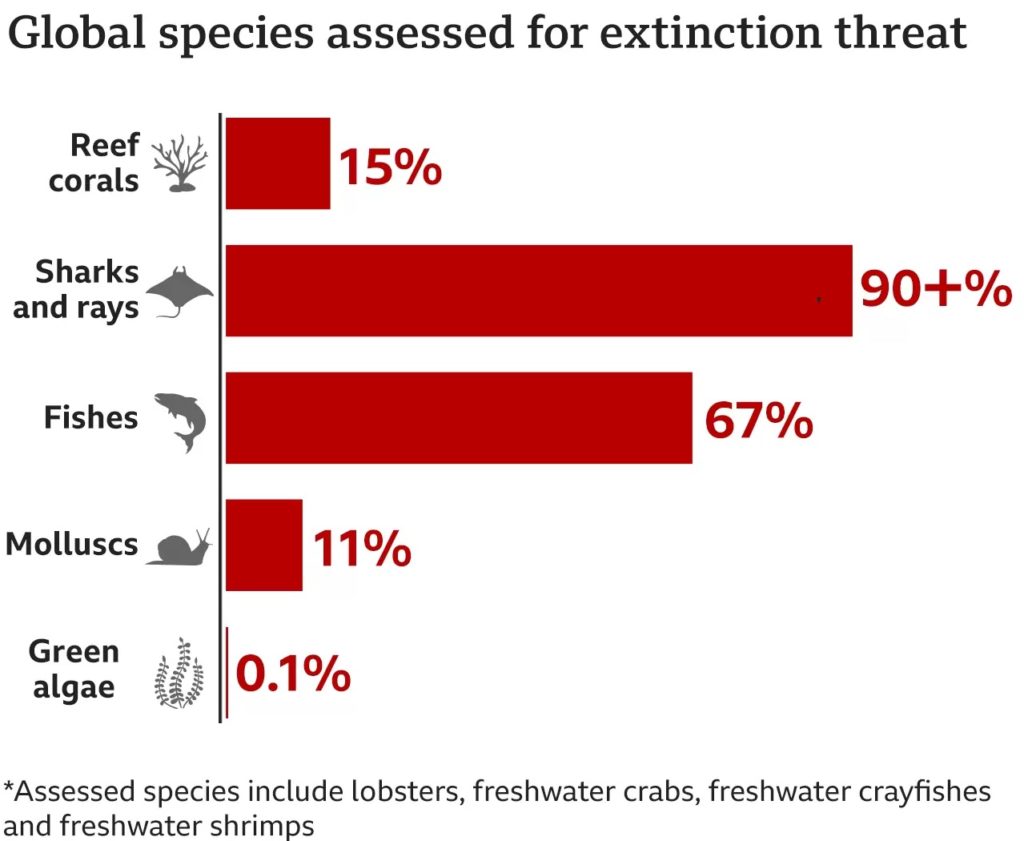

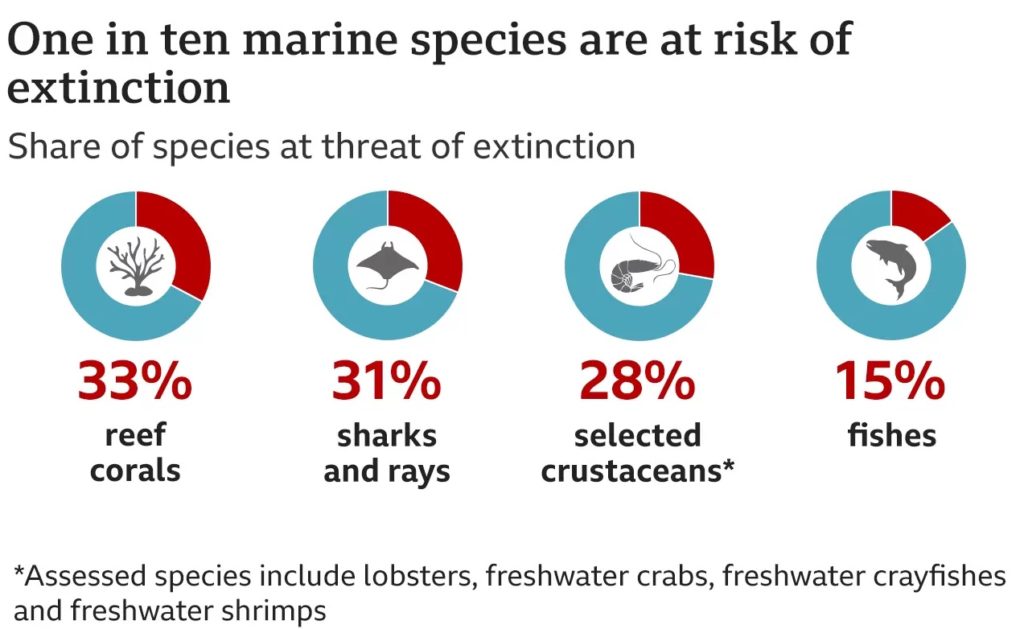

The greatest threat is to the marine biodiversity. According to a study commissioned by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, between 10% and 15% of marine species are already at risk of extinction. Sharks and rays are among the species set to lose out from the failure to pass the treaty. According to the IUCN they are facing a global extinction crisis – and are one of the most threatened species groups in the world. Many migratory species such as turtles and whales move through the world’s oceans interacting with human activities like shipping which can cause them severe injuries and death.

Source: BBC

There are concerns that without this treaty, not only will marine species not be protected but also some species will never be discovered before they become extinct.

A legally binding High Seas Treaty would put limits on how much fishing can take place, restrict the routes of shipping lanes and exploration activities like deep sea mining. It will help in slowing down the pace of deterioration of marine ecosystems and restore their capacity to self-stabilization.

What are the major impediments to the Treaty on High Seas?

The negations have failed to reach consensus on several contentious issues like: (a) Ensuring fair access to marine resources (MGRs) for all. Industrialized nations have technology to access deep sea resources which less-industrialized nations lack. Just 10 industrialized countries account for 71% of fishing catch value and 98% of patents on genetic sequences of marine life in the high seas. Several Latin American nations have criticized richer nations’ rigidity and continued focus on their own narroa economic interests; (b) Principles and procedures to establish Marine Protected Areas (MPAs): They are global common that belong to all countries. No single country can claim exclusive right over high seas and its resources. There has been lack of consensus on framing an overarching mechanism for implementing and managing MPAs, how to integrate them with existing fisheries management policy or how the environmental impacts of planned activities should be assessed; (c) There are also differences regarding funding and support for developing countries. Arctic is an another undecided issue. As Arctic ice melts due to climate change and shorter winters, it will open up new area of extraction. But countries are divided over the activities to be permitted and their impact on Arctic ecosystem.

What are the various marine resources?

Generally, marine resources are divided into three categories; (a) Biotic resources: They include phytoplanktons (algae and diatoms), zooplanktons ,fishes, crustaceans, molluscs, corals, reptiles and mammals etc.; (b) Abiotic resources (mineral and energy): They include (i) Mined Minerals such as salt, sand, gravel, phosphate, diamonds, manganese, copper, nickel, iron, and cobalt; (ii) Drilled Minerals such as crude oil and gas hydrates; (iii) Minerals present in the deep sea waters such as Manganese nodules, Cobalt crusts and Massive sulphides; (c) Commercial resources: This includes navigation, aviation, trade and transport, tourism, livelihood support etc.

| Deep Sea Mining Deep-sea mining is the process of extracting/excavating mineral deposits from the deep seabed. The deep seabed is the seabed at ocean depths greater than 200m, and covers about two-thirds of the total seafloor. Research suggests deep-sea mining could severely harm marine biodiversity and ecosystems. Despite this, there is growing interest in the mineral deposits of the seabed. This is said to be due to depleting terrestrial deposits of metals such as copper, nickel, aluminium, manganese, zinc, lithium and cobalt. Demand for these metals is also increasing in technologies like smartphones, wind turbines, solar panels and batteries. |

What should be the approach going ahead?

The timeline of next round of negotiations is not clear yet, but the deadline has been set for the end of the year.

There is a need to facilitate greater participation to allow all countries and communities (especially costal state, small island and Landlocked developing countries) to have a say in how marine resources existing outside of national jurisdiction should be shared.

Additionally, adjacent coastal states should have a role in decision-making mechanisms pertaining to activities in areas beyond national jurisdiction that affect them.

There is a need to have an effective, reliable mechanism to build capacity and transfer marine technology to the developing nations. It is essential to the success of the treaty.

Conclusion

The marine ecosystems are facing dangers of unprecedented level. Ocean systems are a vital buffer against global warming. They provide a primary protein source for more than 3 billion people, and support the livelihoods of almost 600 million people. Just like atmospheric warming; the window to take actions to protect marine ecosystems, before irreversible catastrophic damages happen, will be limited. The countries must act with urgency to reach consensus to protect marine ecosystems in the earnest. A binding High Seas Treaty is necessary in this regard.

Syllabus: GS II, Bilateral, regional and global groupings and agreements involving India and/or affecting India’s interests; GS III, Conservation, Environmental pollution and degradation.

Source: Indian Express, Down to Earth, BBC, Foreign Policy