ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 19 April. Click Here for more information.

ForumIAS Answer Writing Focus Group (AWFG) for Mains 2024 commencing from 24th June 2024. The Entrance Test for the program will be held on 28th April 2024 at 9 AM. To know more about the program visit: https://forumias.com/blog/awfg2024

Contents

| For 7PM Editorial Archives click HERE → |

Introduction

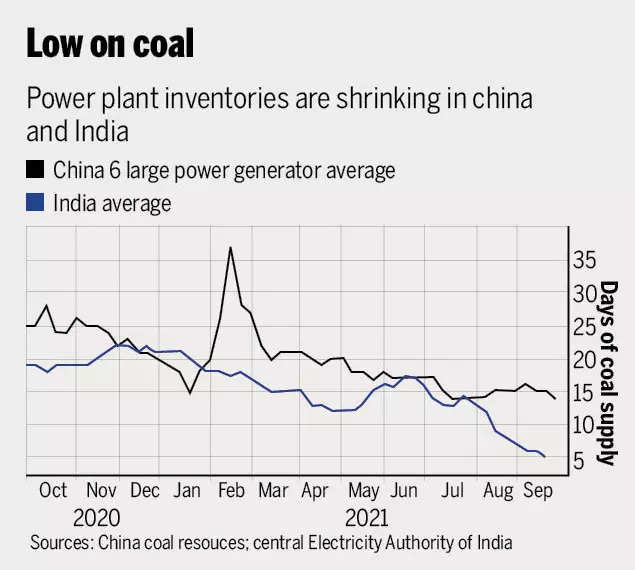

India is staring at a coal crisis as it faces an acute coal shortage. Coal supplies in major plants across the country are at critically low levels. On an average, most power stations had only 3-4 day’s of coal. This is way lower than the government guidelines which recommends supplies of at least 2 weeks.

The shortage of coal is more acute in the non-pithead plants or the plants which are located far off from the coal mines. Such plants account for 98 of the 108 plants that have reached critical level of stocks i.e. under 8 days.

While experts are worried over the crisis, the government on the other hand is of the opinion that rising demand for energy is a positive signal as it means that more households are able to afford electricity, and industries are getting back to pre-pandemic levels.

Let us have a detailed look at the issue.

India’s coal reserves

India is the 2nd largest producer and consumer of coal in the world after China.

There has been a growth of 5.37% in the total estimated coal reserves during the year 2020 over the last year.

The top three states with the highest coal reserves in India are Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, which accounts for approximately 70% of the total coal reserves in the country.

Majority of the produced coal is consumed for electricity generation.

India’s coal fired thermal power plants account for 54% of India’s 388 GW installed generation capacity, Renewable energy (101 GW), Gas (25GW), hydropower (46GW) and nuclear energy account for the rest.

What are the reasons behind the shortage?

Coal crisis is being ascribed to the following reasons:

i). Rise in electricity demand due to the economic revival after the lifting of curbs: Power consumption in the last two months alone jumped by almost 17%, compared to the same period in 2019.

ii). With a delayed and scattered monsoon, coal production was also impacted at CIL’s mines from July onwards. Moreover, heavy rains in September impacted coal production especially in central and eastern India due to severe flooding in mines. This has also impacted certain key logistic routes.

iii). A spike in imported coal prices by more than 40%: China, the biggest consumer and producer of coal, is facing a severe shortage. Therefore, it has effectively put restrictions on the export of coal and is competing for imported coal in the international market. This has led to thermal coal prices and freight costs soaring in the international market, witnessing over a 100% increase this year.

Hence, power plants in India that usually rely on imports are now heavily dependent on Indian coal, adding further pressure to already stretched domestic supplies.

iv). Inadequate stocks at power projects: Power plants used their coal stocks and did not replenish them. They even did not adhere to the CEA guidelines of stocking the coal for 22 days.

v). Lower generation from other fuel sources.

vi). Non-payment of coal dues: Power tariffs are set by the respective states in India and are among the lowest in the world. State-run distribution companies have absorbed higher input costs to keep tariffs steady. This has left many such companies deeply indebted, with cumulative liabilities running into billions of dollars. The companies’ strained balance sheets have consistently triggered delayed payments to power producers, often affecting cash flows and disincentivising further investment in the electricity generation sector.

vii). Also, as part of the largest global household electrification drive through the Saubhagya scheme, the electricity load shot up.

viii). Inadequate mining exploration by CIL and non-CIL entities: Legacy of nationalisation and the long monopoly of government-owned Coal India Limited has resulted in inadequate exploration and mining of the mineral leading to shortage of coal. The production has stagnated and stands at 600 MT for the past three years.

A number of mines were allocated to entities other than CIL. These mines have not augmented coal production. Non-CIL coal production fell from 128 MT in 2019-20 to 120 MT in 2020-21.

-As a major reform, the government has ended Coal India’s monopoly over the commercial production of domestic coal in early 2020. Since then, some coal blocks have been auctioned for commercial use, but it will take time for these blocks to start producing. This is because several clearances have to be obtained before commencing production.

ix). Ideology also has a big role to play in this crisis. In India, coal imports have been traditionally high. Under its atmanirbharta drive, the government has voiced concerns on this issue and asked generators to be more self-reliant. Coal dependency came down over time, which also coincided with a lower phase of economic growth. The same has happened in China where the government has taken the greening concept seriously and asked coal producers to control production and power generators and move over to other greener fuels. This has made coal producers less willing to increase investment.

x). Lack of enthusiasm and participation in the auctions because coal is no longer seen as a fuel of the future.

What is the global scenario?

The supply crunch is being faced not just by India but by China and Europe as well.

– China: The foremost consumer of coal globally is in the grip of a severe shortage of both coal and electricity. Power cuts and blackouts were being experienced by a majority of the areas. Many factories have also shut production temporarily, adding to the problems of an already slowing economy.

– Europe: In the European Union energy costs have skyrocketed. European governments are trying to shield residential and small business customers from the full force of increasing energy prices on utility bills through price caps, rebates and tax cuts.

What is the likely impact of coal shortage?

The coal shortage problem is very serious as it affects power supply, which is the backbone of all economic activity.

i). Delay in economic recovery: Electricity shortages faced by industry could delay India’s economic recovery as businesses might be forced to downscale their production.

ii). Inflationary impact: If coal shortage continues and if companies start importing expensive coal then the cost would be passed down to consumers. This would result in an inflationary impact on the top of already high retail inflation.

iii). Impact on steel: Increase in coal prices will have an impact on steel, the price of which may also go up due to this unprecedented rise. Steel players use coal as fuel to produce power to run plants and produce steel through the directly reduced iron (DRI) route.

iv). Rise in spot prices of power: Spot prices of power sold through the Indian Energy Exchange jumped more than 63% year-on-year in September to average Rs 4.4 ($0.06) a kilowatt hour and were as high as Rs 13.95.

v). Impact on outcome of COP26 at Glasgow: The great hope was that the success of renewable energy in recent years would allow for countries to speed up their transition away from high-emissions fossil fuels — particularly coal. It is hard to see how the news of an economic recovery being hampered by a coal shortage in the two biggest engines of global growth will aid in achieving consensus at Glasgow.

What can be done to improve the situation?

Short term:

– Ramping up production: The government has said it is working with state-run enterprises to ramp up production and mining to reduce the gap between supply and demand. Moreover, with the monsoon on its way out and winter approaching, the demand for power usually falls. So, the mismatch between demand and supply may lessen to some extent.

– Sourcing coal from captive mines: The Centre amended rules to allow 50% sale of coal from captive mines. It will be applicable to both private and public sector captive mines. With this amendment, the government has paved the way for releasing of additional coal in the market by greater utilisation of mining capacities of captive coal and lignite blocks. Availability of additional coal will ease pressure on power plants and will also aid in import-substitution of coal.

Captive mines are operations that produce coal or minerals solely for the company that owns them and under normal conditions are not allowed to sell what they produce to other businesses.

– Penalty mechanism: To avoid a situation where payment defaults of a state lead to supply crisis, the power ministry is devising a penalty for power generation companies (gencos)/states which do not pay Coal India Ltd on time.

– Govt might also decide to divert supplies away from industrial users — like aluminum and cement makers — to prioritise power generation.

– Coal fuelled power generation plants under the corporate insolvency resolution process can be allowed to commence operations immediately, regardless of the stage of the proceedings at NCLT. This will save the coal transport time and quantity limitations in coal transportation to non-pit head coal plants.

– Funds for CIL: CIL, which had reserves of around ₹35,000 crore in 2015, now appears to be strapped for funds, especially cash flows as power generating companies (GENCOs) owe more than ₹20,000 crore to CIL. Funds will have to be arranged for the expansion of existing mines as well as the opening of new ones. For this the following needs to happen:

i). The Union Government should stop squeezing more funds out of CIL as it has done during the past few years by way of dividends to balance its own Budget

ii). Govt should consider providing cash to CIL against the dues owed by GENCOs.

Long term:

These short-term fixes may help to get India through the current coal crisis, but long term measures are required.

– Working with states to boost coal production: CIL should focus on mining. Officers from the Union Government should go down to the States, convey a value proposition and sit with State-level officers to resolve issues related to land acquisition and forest clearances.

– Non- CIL production will have to be augmented.

– There was an inter-ministerial Coal Project Monitoring Group (CPMG), which was set up in 2015 to fast-track clearances, that became dormant. This will need to be revived.

– The financial crisis that is brewing in the power sector needs to be addressed. GENCOs are yet to receive more than ₹2,00,000 crore from distribution companies. They, in turn, owe more than ₹20,000 crore to CIL. There is, hence, a serious cash crunch though most of these entities show profit in their balance sheets.

– An opportunity to transition towards gas: Lastly, the current crisis affords an opportunity to India to push strongly towards this cleaner alternative. India produces 28.6 billion cubic metres (bcm) but the price differential between coal and gas has been steadily narrowing. For the 105 bcm of natural gas India plans to import annually by 2030, the country has already built regasification infrastructure at the ports. It has 39.5 mtpa of capacity, good for 2026, and an additional 30 mtpa is on course to become operational by 2023.

The current coal crisis is a wake-up call for India and the time has come to reduce its over-dependence on coal and more aggressively pursue a renewable energy strategy.