ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 19 April. Click Here for more information.

Contents

| For 7PM Editorial Archives click HERE → |

Introduction

As India is developing and modernising, the Government of India is improving its efforts to help the poorer nations across the world, both towards ending poverty and improving living standards. India’s role in international overseas development cooperation and partnership has undergone significant transformation over the past years. India is now becoming a net donor of development cooperation/assistance from being a chronic beneficiary. However, India’s overseas development assistance and cooperation suffer from various challenges, which must be rectified to enhance its effectiveness.

How has India’s Overseas Development Cooperation evolved over time?

India’s overseas development cooperation began right after the independence. India found its development partnership approach through the ethos of the national movement. Colonization, Apartheid and underdevelopment were among the major challenges in the 1950s. Despite its resource constraints, India offered its development experience to countries which wished to engage.

In 1949, India began with cooperative efforts for Burma and Indonesia, through technical cooperation. This was successful, and became the basis for expansion to several initiatives in Asia and Africa. India’s overseas development cooperation remained unconditional and responsive to partner priorities. It emphasised capacity-building, particularly the development of human resources e.g., India established the Imperial Military Academy in Harar, Ethiopia in 1958. It trained the military officers of several African countries, and showed an early regional approach.

To undertake capacity-building programmes, India launched the Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation (ITEC) Programme in 1964. ITEC offered India’s institutions and experience for sharing. It covered both civilian and military aspects. ITEC initially covered Asian countries, then expanded to Africa and now covers over 150 countries, including in Central Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, and the South Pacific. The ITEC programme has annual budget of ~INR 200 crores.

Over the years, India has contributed to plurilateral funds for achieving these development goals including through the India-Brazil-South Africa, (IBSA) Fund and India-UN Development Partnership.

With the faster pace of development post 1991-reforms, India’s overseas development assistance (ODA) has also picked up pace.

What is the current status of India’s Overseas Development Cooperation/Partnerships?

Funds

According to the dashboard provided by the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), between 2008-2022 (till July) India has allocated funds worth INR 85,059 Crore as grants and loans. Of this, INR 70,221 Crore has been disbursed. India’s Grants and Loans are mostly limited to neighbourhood nations: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, Maldives, Mauritius, Mongolia, Myanmar, Seychelles and Sri Lanka. Bhutan has been by far the biggest recipient of India’s overseas development assistance (ODA) through loans and grants, receiving ~54% (INR 46,196 Crore) of the allocated funds.

In addition, the Government has also provided Lines of Credit (LoCs) worth US$ 22.8 billion between 2014-2022 (till September), with record US$ 7.2 billion worth of LoCs extended in 2016-17. In contrast to grants/loans, India’s overseas development assistance (ODA) through LoCs is more diverse with countries in Africa and Caribbean as the major recipients. According to information available in MEA’s dashboard, India has extended LoCs to 66 nations between 2014-22. According to data available with EXIM Bank, India has provided LoCs worth US$ 28 billion between 2002-03 and 2018-19.

Instruments

India’s overseas development assistance (ODA) is based on a framework with 4 broad elements: (a) Lines of Credit (LOCs) under the Indian Development and Economic Assistance Scheme (IDEAS); (b) Grants and Loans; (c) Capacity-building training programmes especially under the Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation (ITEC) programme; (d) Bilateral grant assistance projects. All overseas partnerships contain some combination of the above, e.g., In Mozambique, support for solar panel production was through three elements: capacity building of scientists through training at Central Electronics, a line of credit for infrastructure support and a grant element.

Besides bilateral projects, the Government has recently taken steps toward triangular cooperation with few developed nations and the UN agencies. Agreements/Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) have been signed with the United States, the European Union, Japan, World Food Programme, the UNDP, etc. Some triangular projects are already being implemented in Afghanistan and Africa.

Depending on the priorities of partner countries, India’s development cooperation ranges from commerce to culture, energy to engineering, health to housing, IT to infrastructure, sports to science, disaster relief and humanitarian assistance to restoration and preservation of cultural and heritage assets.

Institutional Arrangement

India launched the India Aid Mission (IAM) in Nepal in 1952, before the US had established the US Agency for International Development (USAID, 1961). It was later rechristened as the Indian Cooperation Mission (ICM).

India Development Initiative (IDI) was launched in 2003. Subsequently, the Indian Development and Economic Assistance Scheme (IDEAS) was launched in 2005 for managing credit lines. In 2007, the IDI was suspended. A new India International Development Cooperation Agency (IIDCA) was announced to be set up but it was never established.

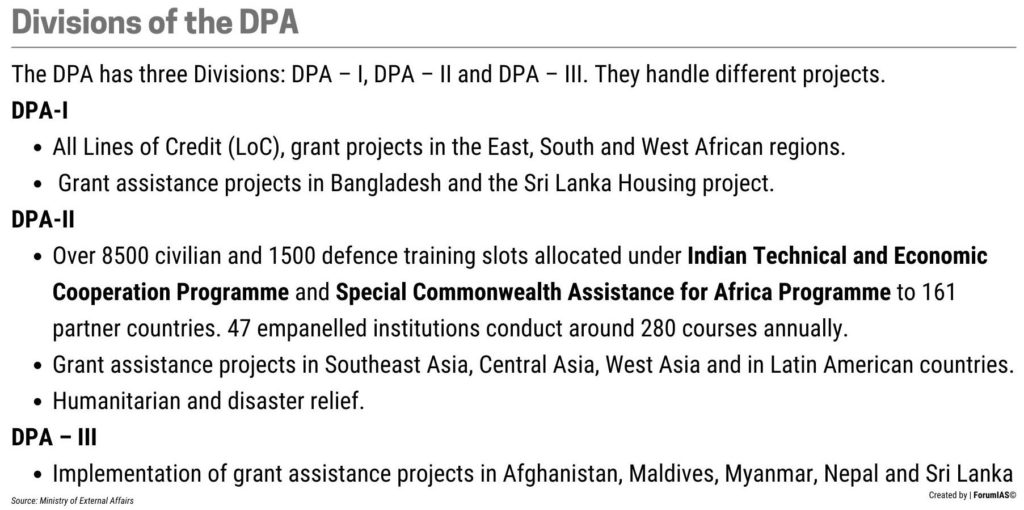

A Development Partnership Administration (DPA) was established within the Ministry of External Affairs in 2012. It has various divisions that handle different projects and regions.

What are the issues in India’s Overseas Development Cooperation?

Institutional Arrangement: India’s overseas development assistance (ODA) programme lacks proper institutional arrangement. The divisions of DPA lack proper structure with overlapping regional and functional jurisdictions. Ideally, divisions could have been made on a regional basis (like Africa, East Asia, Latin America etc.) or functional basis (handling LoCs, Grants, Capacity building programmes).

Institutional Capabilities: The DPA also struggles with lack of capabilities to implement the projects. Project implementation in foreign nations faces several challenges like statutory approvals and clearances. There is a need for constant monitoring and coordination with agencies of foreign countries. Similarly, there are internal constraints like ensuring the adequacy and predictability of budget allocations, approval/appraisal procedures with Ministry of Finance, selecting competitive firms from India to undertake projects abroad etc. Addressing these challenges require specialised skills. DPA is lacking in such capacity when compared to other agencies like the USAID.

Transparency: There is lack of transparency and visibility in terms of allocations and outcomes. There is no central database that can provide a comprehensive visibility on all the grants/LoCs extended, projects undertaken or the capabilities developed abroad. The lack of information in public domain limits review and establishing efficacy of the India’s cooperation efforts. This, in turn, undermines the accountability of the Government’s initiatives.

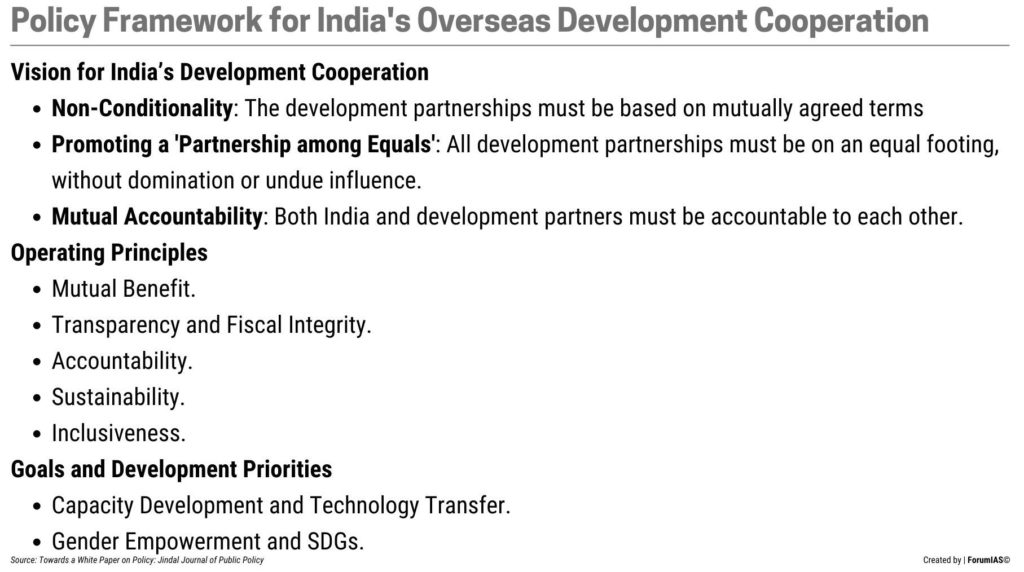

Approach: There is no stated policy on India’s overseas development cooperation. This leads to lack of consistency in methods of assistance/cooperation, selection of projects, or allocation of funds. This is in contrast to Japan’s ODA or China’s BRI.

What should be the approach going ahead?

Policy and Vision: Foreign Policy experts suggest that the Government must bring out a policy on India’s Overseas Development Cooperation, stating its vision, objectives, principles and goals. This will replace the current ad-hoc approach and make India’s cooperation more objective. Some experts even suggest enacting an India Overseas Development Cooperation Act, to enable Parliament’s oversight over the cooperation programme. This is similar to UK’s International Development Act (2002) which detailed the country’s objective to contribute towards global poverty reduction. The UK was one of the first countries to provide aid without being tied to any domestic policy considerations, making the 2002 Act an effective and successful framework.

Autonomous Body: There is a need to establish an autonomous agency to undertake the cooperation activities abroad. DPA in its current form lacks adequate authoritative powers. The US AID is an independent agency of the US Federal Government established under the the Foreign Assistance Act (1961). The DPA can be made a more autonomous entity empowered to address long-term and short-term strategies. The Brazilian Cooperation Agency, affiliated to the country’s foreign ministry, has a mandate to negotiate, coordinate, implement and monitor technical cooperation projects and programmes. Similar powers should be accorded to the DPA.

Enhance Visibility: There is a need to enhance visibility on the all the projects undertaken with the corresponding spending. A comprehensive database should be developed. The present dashboard only lists year-wise allocation/disbursal of funds, but provides no details of projects. Proper visibility will enable analysis, periodic review and revision of India’s international development cooperation policy.

Widen Cooperation: The Government can also move beyond government-to-government negotiations and agreements to include more plural and diverse stakeholders like representatives from the private sector, academia, philanthropic institutions and civil society. Collaborations with the private sector and civil society can be achieved by engaging with existing platforms such as the Forum for Indian Development Cooperation (FIDC) (an initiative by the DPA, academia and civil society organisations, and launched in 2013) that has been working to raise awareness on various dimensions of development cooperation policies through public engagement at the domestic level.

Sharing Domestic Capabilities: Going forward, India should actively promote learnings from its domestic initiatives like Aadhar, JAM Trinity, Ayushman Bharat, CoWin, UPI etc. in other developing countries and help them achieve development outcomes.

Conclusion

India’s overseas development cooperation and assistance initiatives have enabled India to win goodwill, especially among developing countries. India’s programmes have been successful because of the equal involvement of the partners as well as non-conditionality of India’s cooperation. Now the Government must focus on reforms to make the programme more structured. This will enable India to play a more constructive role in reshaping the global order which is going through a phase of uncertainty.

Syllabus: GS II, India and its neighbourhood relations.

Source: Indian Express, ORF, Money Control, Ministry of External Affairs, Indian Council on Global Relations