ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 19 April. Click Here for more information.

ForumIAS Answer Writing Focus Group (AWFG) for Mains 2024 commencing from 24th June 2024. The Entrance Test for the program will be held on 28th April 2024 at 9 AM. To know more about the program visit: https://forumias.com/blog/awfg2024

Context:

With growing concerns over sea-bed mining, parties to UNCLOS started negotiations to agree a treaty to protect the biodiversity of high sea and promote sustainable use of resources.

What is seabed mining?

- Seabed mining is the process which involves extracting submerged minerals and resources from the sea floor, either by dredging sand or lifting material in any other manner.

- Although the distinction between shallow-water mining and Deep Sea Mining (DSM) is not formally demarcated, an emerging consensus says that DSM is the removal of minerals from sea beds deeper than 500 meters.

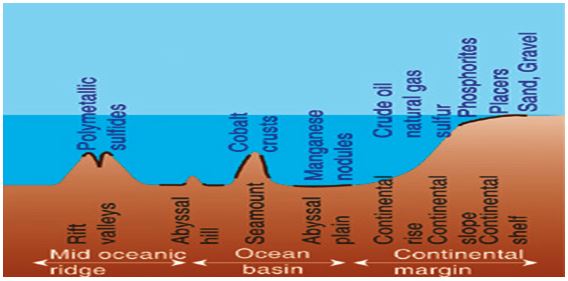

- Three forms of DSM have attracted the attention of companies – the mining of cobalt crusts (CRC), polymetallic nodules, and deposits of seafloor massive sulphides (SMS) also known as Polymetallic Sulphides

Types of metal deposits in the deep sea

International developments

- Canadian mining company Nautilus Minerals became the first to bring off the deep sea mining (DSM) operation. The Bismarck Sea in Papua New Guinea has been marked out as the testing ground. It is also carrying out exploration activities for Tonga, Fiji, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu.

- Sudan and Saudi Arabia are working together to start underwater mining in the Red Sea, believed to have one of the largest polymetallic sulphide deposits in the world.

- The U.S., as a non-party to UNCLOS and ISA, has issued exploration leases on its own to Ocean Minerals Company (OMCO), a subsidiary of defence contractor Lockheed Martin, to explore for nodules in the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ)

- China and South Korea has held contracts to explore SMS deposits in international waters of the Indian Ocean. Russia and France hold exploration leases on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

- In May 2018, 7th Annual Deep sea mining Summit was held in London to discuss the economic landscape, growth and prospects of deep sea mining. The 8th Annual Asia- Pacific Deep sea mining summit will take place in November 2018.

Why seabed mining?

- The quantity of minerals occupying the ocean floor is potentially large. Seabed mining is concerned with the retrieval of these minerals to:

- Ensure security of supply. For example: Studies have shown that retrieving even 10% of the oceanic reserves can allay India’s energy crisis for up to 100 years.

- Fill a gap in the market where either recycling is not possible or adequate, or the burden on terrestrial mines is too great.

- Advantages over terrestrial mining:

- There is no need to construct permanent physical mine and transport infrastructures.

- Assets like surface vessels and platforms are reusable.

- There is no use or pollution of fresh water sources

- Limited or no effect on local communities (depending on the distance from shore)

- Metal grades and quantities are often higher than terrestrial ores

Regulation and Management:

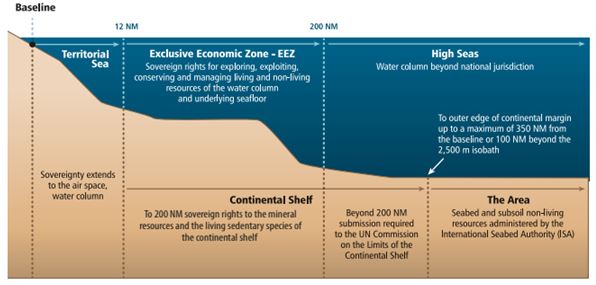

- The legal framework governing anthropogenic activity on the ocean depends upon distance from land. A coastal state’s territorial sea, in accordance with the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), extends to 12 nautical miles (22 km) from its coastline and includes the air space, the water body to the seabed and the subsoil

- Coastal states have exclusive rights and jurisdiction over the resources within their 200-nautical mile (370 km) exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

- Beyond the national jurisdiction, the ocean seabed and water above is termed as “Area”. UNCLOS designates the “Area” as the common heritage of mankind.

- Three sections in UNCLOS are particularly relevant to deep sea mining: Article 136 (Common Heritage of Mankind) , Article 137.2 (Legal Status of the Area and Its resources) , and Article 145 (protection of the marine environment)

Role of International Seabed Authority (ISA):

- The ISA was established in 1982 by UNCLOS and is an autonomous intergovernmental body with 167 members.

The ISA is responsible for the mineral resources and the marine environment in the Area. - The ISA considers applications for exploration and exploitation of deepsea resources from contractors, assesses environmental impact assessments and supervises mining activities in the ‘Area’.

Sea Bed Mining and India

Deep Ocean Mineral Resources of India

- India’s exploration area has an estimated resource of about 100 million tons of strategic metals such Copper, Nickel, Cobalt besides Manganese and Iron. A First Generation Mine-site (FGM) with an area of 18,000 sq km has been identified.

- 380 million tonnes of nodules are present in the licensed exploration area. These include 92.60 million tonnes of manganese. Minerals like cobalt, nickel and copper are present in the concentrations of 0.56, 4.70 and 4.30 million tonnes.

Initiatives:

- In 1981, the first nodule sample from Arabian Sea was collected by first research vessel Gaveshani. Later a program on polymetallic nodules was initiated at CSIR-NIO

- In 1987, India was recognized as a “pioneer investor” by ISA and given the pioneer area for exploration of deep-sea mineral (polymetallic nodules) in the Central Indian Ocean Basin.

- In 2002, India entered into a 15-year contract with the International Seabed Authority (ISA) for pursuing developmental activities for polymetallic nodules in the Indian Ocean.

- In 2012, India launched Polymetallic Nodule programme for exploration and development of technologies for harnessing of nodules from the Central Indian Ocean Basin (CIOB) allocated to India by ISA.

- In 2013, deep sea exploration ship ‘RV Samudra Ratnakar’ built by Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI)(South Korea) for Geological survey of India went for sea trials

- It has 4 components viz. Survey & Exploration, Environmental Impact Assessment, Technology Development (Mining), and Technology Development (Metallurgy).

- In 2016, India signed a 15 year contract with ISA to get exclusive rights to conduct exploration in a 10,000sq. km location near Rodrigues Triple Junction (RTJ) – a junction in the Southern Indian Ocean near Mauritius where three tectonic plates meet.

- The exclusive exploration rights were further extended by 5 years in 2017

- In 2018, the Union government unveiled the blueprint of India’s Deep Ocean Mission

About Deep Ocean Mission:

- The mission proposes to explore Deep Ocean similar to space exploration started by ISRO.

- The Centre has drawn up a plan for 5 years and seeks to invest Rs. 8,000 crore

- Key areas of the mission are:

- Deep-sea mining

- Ocean climate change advisory services

- Underwater vehicles

- Underwater robotics related technologies

- Two key projects have been planned under the Mission:

- Desalination plant powered by tidal energy

- Submersible vehicle equipped to explore depths of at least 6,000 metres

Environmental Concerns associated:

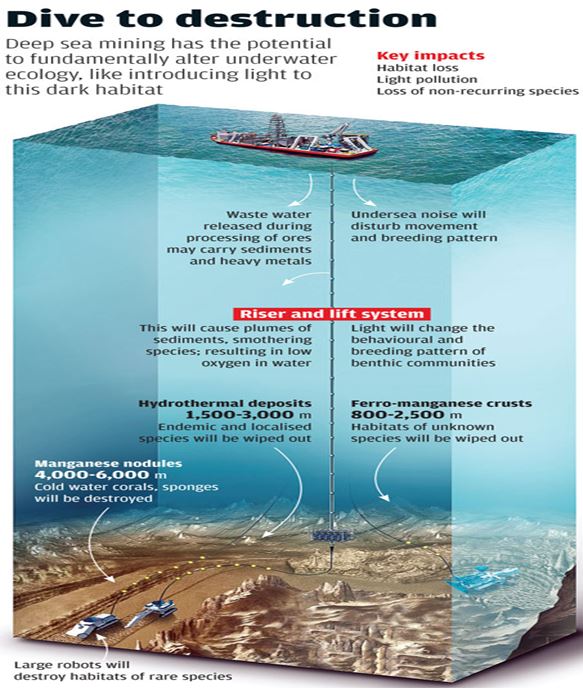

Given our poor understanding of deep sea ecosystems, growing industrial interest, rudimentary management, and insufficient protected areas, the risk of irreversible environmental damage is of serious concern.

- Seabed mining would harm marine organisms, disrupt marine ecosystem, thereby impacting the rich biodiversity of oceans in the following ways:

a) Mining of hydrothermal vents would destroy an extensive patch of productive vent habitat. Mining is also expected to alter venting frequency and characteristics on surrounding seafloor areas, affecting ecological communities far beyond the mined site.

b) Cobalt-rich crust mining would involve cutting 5-8cm of the crust on the top of seamounts, and could thus have a significant impact on corals, sponges and other benthic organisms associated with seamounts. The sediment plumes created could also impact these and other suspension feeders ‘downstream’ from the mining operations.

c) Mining of polymetallic nodules will also have devastating effect on the marine biodiversity associated with oceanic ridges.

d) Extraction of gas hydrates from seabed reserves carries potentially considerable environmental risk. The greatest impact would be accidental leakage of methane during the dissociation process. Other possible impacts of methane hydrate extraction include subsidence of the seafloor and submarine landslide

2. Increased Noise: Submerged remotely operated vehicles will increase underwater ambient noise. Anthropogenic noise is known to impact a number of fish species and marine mammals by inducing behaviour changes, masking communication, and causing temporary or permanent damage to hearing

3. Anthropogenic Light: Increased light may attract or deter some fish or benthic species and alter their feeding and reproductive behaviours.

4. Waste Water Release: As the ores mixed with seawater are processed in surface support vehicles for extracting minerals, this will create massive swirls of debris and sediments. Further, the treated seawater, of different salinity and temperature and containing trace amounts of toxic chemicals, when dumped in the sea, will have profound impacts on the ecosystem.

Seabed Mining and Geopolitics

The recent developments in the arena of deep sea mining exemplify the growing interest and quest for mineral extraction from the ocean. Deep-sea mining does not only have an economic dimension but is considered to be an effective means of accessing and monitoring international or disputed waters and thus serves as a political tool. Further, since deep sea mining is carried on beyond the EEZ of nations in the ‘Area’, there is apprehension that whichever country explores the concerned area will eventually have a strategic influence in the region.

Quest of minerals as a political tool

A number of countries like China, Japan, South Korea and India are pursuing the requisite technology for deep-sea mining operations. Japanese interests in seabed mining highlight one of the political reasons for developing sea mining operations. Japan is a large producer of high-tech electronics that require rare earth elements for manufacturing. However, China which contributes nearly 90% of global production of REE has been alleged of using this monopoly to control the production and price of REE thus hampering Japanese industries. Thus, Japan has been trying to explore deep sea minerals to reduce its import dependence on China.

India’s concerns over Chinese explorations

There have been concerns that deep-sea mining exploration could spread China’s influence in the South China Sea, the East China Sea and the Indian Ocean. In 2011, when International Seabed Authority approved China’s bid to explore a 10,000-square-kilometer area in the southwest Indian Ocean for a total of 15 years, India considered it as foreign encroachment near its territory and alleged concerns over China using exploration for strategic interests.

Steps to be taken:

- It is imperative for India to survey and predict the ocean environment, map the sea bed, evaluate the rich and economically viable deposits of polymetallic nodules, heavy metals, fossil placers and phosphorite deposits. Further, advanced indigenous technology and human resource should be developed to sustainably use ocean mineral resources, while ensuring minimal damages to the marine environment.

- Mitigation techniques to address environmental concerns

- Mitigation techniques that have been proposed to monitor the potential impacts to biodiversity and aid recovery of mined areas are still being researched and remain untested.

- According to Scholar Van Dover (2014), possible measures may include:

a) Avoidance (such as by establishing protected reserves within which no anthropogenic activity takes place),

b) Minimization (such as by establishing un-mined biological corridors, relocating animals from the site of activity to a site with no activity, minimizing machine noise or sediment plumes)

c) Restoration (as a last resort, because avoidance would be preferable).

3. Environmentalists are of the opinion that improving consumer access to recycling and streamlining manufacturing processes can be a more efficient and economically viable method of sourcing metals than mining ores on land/ sea and could greatly reduce or even negate the need for exploitation of seabed mineral resources.

4. Civil society groups such as Deep Sea Mining Campaign, MiningWatch Canada, Greenpeace, Earthworks, and the Center for Biological Diversity have been making efforts to make the international community aware about the potential environmental threats of seabed mining.

5. Way forward for ISA:

- The ISA considers benefits of sea bed mining in a narrow sense and takes into account only economic or financial benefits. It should adopt broader understanding of the notion of benefit to include “total economic value”, which encompasses both the direct and indirect values of natural resources and reinterpret benefit in the lines of Sustainable Development Goals.

- The ISA should take into account relevant multilateral environmental agreements to represent the interest of future generations and counterbalance the commercial interest in deep seabed mining.