ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 19 April. Click Here for more information.

ForumIAS Answer Writing Focus Group (AWFG) for Mains 2024 commencing from 24th June 2024. The Entrance Test for the program will be held on 28th April 2024 at 9 AM. To know more about the program visit: https://forumias.com/blog/awfg2024

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 What was the original proposal regarding TRIPS IP Waiver?

- 3 Why has India demanded a complete TRIPS IP waiver?

- 4 Why are the arguments against a complete TRIPS IP waiver?

- 5 What are the details of the agreed proposal?

- 6 What is Compulsory Licensing?

- 7 What are the shortcomings associated with the new proposal?

- 8 What other steps have been taken to increase availability of COVID-19 Vaccine?

- 9 What more should be done?

- 10 Conclusion

| For 7PM Editorial Archives click HERE → |

Introduction

The pandemic has tested the resilience of the global community on various fronts such as whether it can unite to ensure the availability of COVID-19 medical products for everyone. In this regard, India and South Africa, in October 2020, gave a clarion call at the World Trade Organization (WTO) demanding that key provisions of the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement be temporarily waived. The developed world, especially the European Union (EU), kept dragging its feet on this while the virus raged on. Now, after long discussions, a deal has been brokered between the EU, the U.S., India, and South Africa on the issue of the TRIPS IP waiver. This deal will now be presented to the entire WTO membership to be accepted at the forthcoming ministerial meeting. However, this deal is a classic case of too little, too late, and represents a significant climb down from the original proposal of India and South Africa.

What was the original proposal regarding TRIPS IP Waiver?

India and South Africa contended that the application and enforcement of intellectual property rights (IPRs) were hindering timely provisioning of affordable medical products to the patients. They argued that ‘rapid scaling up of manufacturing globally’ was an obvious crucial solution to address the timely availability and affordability of medical products to all countries in need. To ensure this, IPRs must be waived for at least 3 years and medical products should be treated as global public goods.

Why has India demanded a complete TRIPS IP waiver?

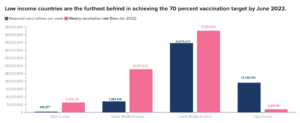

First, there are grave inequalities in vaccine availability and access across different countries. Data from Oxfam International reveals that, as of May 2021, people in the G-7 countries were 77 times more likely to have been vaccinated than those living in the world’s poorest nations. As of 30 January 2022, more than 3 billion people around the world were still waiting to receive their first COVID-19 vaccine dose. (UNDP)

In case of Low Income Countries, the vaccination rate is only 10% of the target rate. For High Income Countries the vaccination rate is 1430% more than the target rate. (Source: UNDP)

Second, the ethical principles of non-maleficence and justice are violated if developed countries deprive other countries of access to vaccines.

Third, the fundamental rights of life and liberty are basic human rights and should take precedence over ownership and property rights, especially in times of a health emergency.

Why are the arguments against a complete TRIPS IP waiver?

First, patents deliver economic growth by preventing infringement of intellectual property and making inventions profitable. Complete waiver leaves little incentive for producers to innovate and produce that good.

Second, pharma companies are business entities aiming for profit. They cannot be expected to act in a completely altruistic manner.

What are the details of the agreed proposal?

The draft ‘compromise outcome’ adopts the approach that the EU has been proposing all along — namely, granting compulsory licences to enhance vaccine production.

According to the draft, countries are no longer required to honor Article 31(f) of TRIPS. Article 31(f) requires countries to ensure that products produced under a compulsory license are predominantly for the domestic market. The draft waiver allows countries to export any proportion of vaccines to eligible countries. However, this waiver is subject to several notification requirements: (a) Eligible members are obligated to prevent re-exportation of COVID-19 vaccines that they have imported; (b) The eligible countries which issue a compulsory license for COVID-19 vaccines have to notify certain details to the WTO. These include information about the entity that has been authorized to produce the product, the quantities, duration, and the list of countries to which the vaccines are being exported; (c) WTO members would be able to issue compulsory licences even if their domestic patent laws do not have the provision to issue compulsory license. Compulsory licences can even be granted using executive orders, emergency decrees, and judicial or administrative orders.

What is Compulsory Licensing?

Compulsory licensing(CL) is a process that allows governments to license third parties (that is, parties other than the patent holders) to produce, use and sell a patented product or process. By that, producers can manufacture patented drugs without the requirement of consent of patent owners. The WTO’s agreement on intellectual property –TRIPS allows countries to issue compulsory licenses to domestic producers.

In India, Compulsory licensing is allowed and regulated under the Indian Patent Act, 1970. Section 84 of the (Indian) Patent Act,1970 provides that after three years from the date of the grant of a patent, any person can apply for the compulsory license, on certain grounds: (a) The reasonable requirements of the public with respect to the patented invention have not been satisfied; (b) The patented invention is not available to the public at a reasonably affordable price; (c) The patented invention is not used in the territory of India.

Compulsory licenses can also be granted under exceptional circumstances.

Section 92 of the (Indian) Patent Act,1970: It authorizes the Union Government to issue a compulsory license at any time after the grant of the patent, in the case of: (a) National emergency; (b) Extreme urgency; (c) Case of public non-commercial use.

What are the shortcomings associated with the new proposal?

First, the draft new waiver includes only COVID-19 vaccines and excludes other COVID-19 medical products. This is a major handicap as medicines also play an equally important role in combating the pandemic.

Second, the draft waiver proposes to waive only patents and not other IP rights. India’s original stand was that all IP rights, not just patents, be waived. The accessibility of COVID-19 medical products will be held up in absence of waiver.

Third, there are multiple procedural requirements which the countries need to fulfill with respect to the WTO if they grant a waiver. This will increase the transaction costs and may deter countries from using the system. Moreover, these conditions are over and above those mandated by TRIPS.

Fourth, the draft waiver is not universal. Only those developing countries that exported less than 10% of world exports of COVID-19 vaccine doses in 2021 are covered for exportation and importation. There is no mention of least developed countries.

Fifth, when compulsory licences are granted, the patent holder receives adequate remuneration, but “transfer of know-how is not ensured”. This would make it difficult to scale up production of COVID-19 vaccines, medicines, and medical devices in the developing world. This will constrain their availability at affordable prices.

What other steps have been taken to increase availability of COVID-19 Vaccine?

The Open Covid Pledge: Several companies came together for ‘The Open Covid Pledge’, which hands out “non-exclusive and royalty-free” licences for covid products.

It provides an open framework under which patent holders can voluntarily pledge not to assert the exclusivity of their rights to manufacture, use, sell, reproduce and import these products.

Covax initiative: It is an initiative led by the World Health Organization, Gavi the Vaccine Alliance and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. It aims to ensure rapid, fair and equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines for all the countries around the world.

What more should be done?

First, considerable support should be given to the vaccine manufacturers by government and nonprofit organizations. For instance, the Indian Council of Medical Research provided funding for covid vaccine development. Similarly, Pune-based Serum Institute of India developed a vaccine for meningitis for use in Africa. Development occurred with help from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Path, a non-profit group that works for health equity.

Second, governments should commit to purchase vaccines from manufacturers in advance, thereby directing research resources at clearly targeted goals and appropriate projects. For instance, Operation Warp Speed in the US led to the rapid development and roll-out of COVID-19 vaccine—by assuring pharma companies decent profits.

Third, vaccines could be bought at an international level (say by the United Nations or World Bank) for developing countries. They would pay a single price and then payments could be collected from these countries depending on their income levels. This will help in countering the adverse effects of monopoly pricing.

Fourth, Patent pools can be used to improve vaccine access by coordinating the actions of complementary patent holders. Similarly, reference pricing may be used by governments to reduce the prices of branded as well as generic drugs and vaccines.

Fifth, countries can use their competition laws to restrict patent abuse. For instance, India’s Competition Act of 2002 can be used to examine whether the high price or inadequate availability of a drug is the result of anti-competitive practices or ‘abuse of a dominant position’.

Conclusion

Domestic patent laws and international conventions must aim to foster innovation. But at the same time, they should not have the effect of reducing vaccine accessibility in instances of dire need, as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. These two should not be looked upon as separate government policies, but must act in a complementary manner, with the balance shifting in accordance with the state of public health in the country.