ForumIAS announcing GS Foundation Program for UPSC CSE 2025-26 from 19 April. Click Here for more information.

ForumIAS Answer Writing Focus Group (AWFG) for Mains 2024 commencing from 24th June 2024. The Entrance Test for the program will be held on 28th April 2024 at 9 AM. To know more about the program visit: https://forumias.com/blog/awfg2024

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 What is the Karnataka-Maharashtra Border Dispute?

- 3 What are the reasons for the Inter-State Border Disputes?

- 4 What steps have been taken to resolve the Karnataka-Maharashtra Border Dispute?

- 5 What are the Constitutional Provisions to resolve Inter-State Border Disputes?

- 6 What are the implications of the Inter-State Border disputes?

- 7 What should be the approach for settling Inter-State Border Disputes?

- 8 Conclusion

| For 7PM Editorial Archives click HERE → |

Introduction

The Karnataka-Maharashtra Border Dispute has escalated with reports of violence in both States, attacking vehicles of other State. The border dispute has its origins in the States’ reorganization in 1956 and has flared up every now and then since 1960s. The matter is already under adjudication of the Supreme Court. However, in the absence of any judicial settlement so far, the dispute has been exploited for political mobilitization. In this context, there is a need for peaceful settlement acceptable to all stakeholders, either through Judiciary or through the intervention of the Union Government.

What is the Karnataka-Maharashtra Border Dispute?

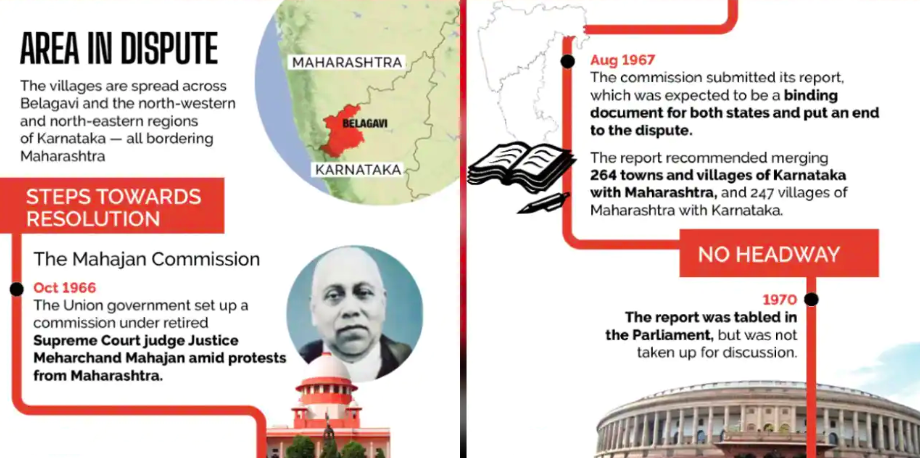

The Karnataka-Maharashtra Border Dispute has its origins in the reorganisation of states along linguistic lines via the State Reorganisation Act, 1956. Since its creation on May 1, 1960, Maharashtra has claimed that 865 villages, including Belagavi (then Belgaum), Carvar and Nipani, should be merged into Maharashtra. These regions have a significant Marathi-speaking population. Karnataka, however, has refused to part with its territory. On the other hand, some villages in Maharashtra want to join Karnataka. In November 2022, all 40 gram panchayats of the Jath taluk in Sangli district of Maharashtra, passed a resolution to join Karnataka. The Government of Maharashtra has submitted a petition challenging certain clauses of the State Reorganisation Act of 1956.

Genesis of the Dispute: The erstwhile Bombay Presidency, a multilingual province, included the present-day Karnataka districts of Vijayapura, Belagavi, Dharwad and Uttara-Kannada.

In 1948, the Belgaum municipality requested that the district, having a predominantly Marathi-speaking population, be incorporated into the proposed Maharashtra state. The States Reorganisation Act of 1956, divided states on linguistic and administrative lines. The Act made Belgaum and 10 talukas of Bombay State a part of the then Mysore State (renamed Karnataka in 1973).

Views of Maharashtra: Maharashtra has demanded realignment of its border with Karnataka. It invoked Section 21 (2)(b) of the State Reorganisation Act, submitting a petition to the Union Ministry of Home Affairs stating its objection to Marathi-speaking areas being included in Karnataka. It claimed 814 villages and the three urban settlements of Belagavi, Karwar and Nippani as part of the Bombay Presidency before Independence. It filed a petition in the Supreme Court in 2004, staking a claim over Belagavi.

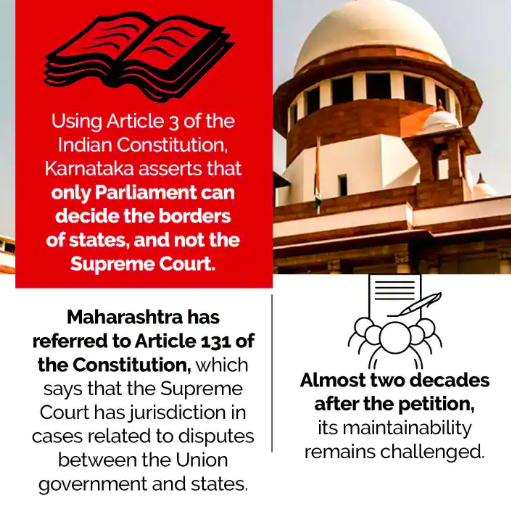

Views of Karnataka: Karnataka has consistently argued that the inclusion of Belagavi as part of its territory is beyond dispute. It has cited the demarcation done on linguistic lines as per the Act and the 1967 Mahajan Commission Report to substantiate its position. Karnataka has argued for the inclusion of areas in Kolhapur, Sholapur and Sangli districts (falling under Maharashtra) in its territory. From 2006, Karnataka started holding the winter session of the Legislature in Belagavi, constructing a massive Secretariat building in the district headquarters on the lines of the Vidhana Soudha in Bengaluru to reassert its claim. Karnataka asserts that only Parliament can decide the borders of States (Article 3 of the Constitution). Maharashtra has referred to Article 131 of the Constitution, which says that the Supreme Court has jurisdiction in cases related to disputes between the Union Government and States.

Source: MoneyControl

What are the reasons for the Inter-State Border Disputes?

Linguistic Identities: Several inter-state border disputes have their roots in the reorganisation of states in the 1950s, which was primarily based on language; language is now tied to the State identity. As a result, there have been a border disputes between Karnataka and Maharashtra, Karnataka and Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Telangana and so on.

District Boundaries: Many of these State boundaries were based on district boundaries established by the British instead of village boundaries. Borders are associated with maps. If a map is not laid out in minute detail where the administrative border stands, it can lead to a disagreement.

Colonial Cartographies: Most States boundaries have been constructed out of colonial cartographies on the basis of host states. They rarely recognise the socio-cultural liminality of borders.

Complex Topography: The topography has also been a source of difficulty; in many locations, rivers, hills, and forests span the border between two states, and the line itself cannot be physically demarcated. On their maps, colonial cartographers often labelled enormous tracts of land as “thick forests” or “unexplored.” Indigenous communities were, for the most part, left alone.

What steps have been taken to resolve the Karnataka-Maharashtra Border Dispute?

Union Government: (a) Mahajan Committee: The Union Government constituted the Mahajan Committee in 1966 to assess the situation. Representatives from both Maharashtra and Karnataka (then Mysore) state were part of the committee. The panel submitted its report in 1967. It recommended to to merge 264 cities and villages of Karnataka with Maharashtra (including Nippani, Nandgad, and Khanapur), as well as 247 villages of Maharashtra (including South Solapur and Akkalkot) with Karnataka. The Report was presented to the Parliament in 1970 but was not taken up for discussion; (b) The Setalvad Study Team on Centre-State Relationships (Part of Administrative Reforms Commission): It strongly recommended establishment of an Interstate Council. It said, “Inter-state disputes need to be settled quickly and impartially; otherwise, they become festering sores that create friction, prevent development, give a perverse direction to the energies of people and governments, and generate hard feelings on all sides“; (c) Union Government Affidavit: In 2010, the Union Government in its affidavit had stated that the transfer of certain areas to then Mysore (now Karnataka) was neither arbitrary nor wrong. It had also underlined that both Parliament and the Union Government had considered all relevant factors while considering the State Reorganisation Bill, 1956, and the Bombay Reorganisation Bill, 1960.

Source: MoneyControl

States: (a) In 1960, a 4-member committee was formed by both States, but it couldn’t arrive at a consensus. Representatives submitted reports to their respective State Governments. In the subsequent decades, Chief Ministers of both States have met several times to find an amicable solution but have failed to settle the dispute; (b) In 2004, Maharashtra approached the Supreme Court challenging certain clauses of the State Reorganisation Act.

Supreme Court: The Supreme Court has observed that the issue should be handled via mutual dialogue. The Supreme Court is still hearing the case.

What are the Constitutional Provisions to resolve Inter-State Border Disputes?

The Constitution of India contemplates a variety of mechanisms for the settlement of Inter-State disputes.

Article 3: The Parliament has the power to alter the border of any State.

Article 131: It creates a judicial mechanism for dealing with Inter-State Disputes. The Supreme Court has original Jurisdiction to adjudicate any dispute between two and more States. The Jurisdiction is extremely wide and includes Inter-State Border Disputes.

Article 263: In Article 263, there is provision for the formation of an Inter-State Council. The President can create an Inter-State Council for inquiring into and advising upon disputes between States.

However, there is no explicit provision for boundary disputes similar to Article 262 for settlement of water disputes.

What are the implications of the Inter-State Border disputes?

Politicization of Disputes: Inter-State Border Disputes become an avenue of political mobilization. Political parties raise popular passions to reap electoral benefits. It becomes beneficial for parties to prolong the dispute, which hampers efforts for peaceful settlement.

Law and Order: Often political mobilization results in violence among the communities in border areas e.g., in the ongoing Karnataka-Maharashtra Border Disputes, buses/vehicles from the other States were targeted in both States. Blockades, restriction on free movement of goods from other States have economic implications as well.

Neglect of Disputed Regions: Uncertainty about the status of the disputed regions in future generally deters the State Governments from undertaking development activities in these regions. There is infrastructure deficit, lack of investments as well as neglect of basic facilities. This also leads to poor human development.

Trust Deficit: It leads to trust deficit between leaderships of the disputing States. It prevents cooperation and hampers the spirit of Cooperative Federalism.

What should be the approach for settling Inter-State Border Disputes?

Legal Settlement: The Supreme Court should take a more proactive approach in settling the Inter-State Disputes. The Karnataka-Maharashtra Border Dispute has been pending since 2004 (18 years). States should also abide by the Supreme Court Judgments.

Inter-State Council: The ISC has been reconstituted in May 2022. The Council should be enabled to play a more proactive role in Centre-State/Inter-state cooperation and dispute settlement. Settlement of all Inter-State Disputes (include water disputes) should be a mandate of the Council.

Pragmatic Approach: The State Governments/Political Parties also need to adopt a more pragmatic approach keeping national interest above all. Dispute Settlement requires a give-and-take approach, and States/Parties should be ready to compromise in peaceful settlement. Union Government should support the constructive efforts.

Address Local Concerns: All Stakeholders (Union Government, State Governments, Political Parties) should be mindful of the concerns of the local residents and should settle disputes taking into account their interests.

Conclusion

The violence ensuing amidst the Karnataka-Maharashtra Border Dispute is most unfortunate. Political parties need to realize that parochial/narrow approach may lead to short-term benefits but impacts national interests in the longer term. Hence it is best to settle such disputes through a pragmatic approach. The Supreme Court should also be more proactive in settling such disputes, rather than letting them fester for long.

Syllabus: GS I, Post-independence consolidation and reorganization within the country, Regionalism; GS II, Issues and challenges pertaining to the federal structure.

Source: Indian Express, The Hindu, The Times of India, MoneyControl